1. Introduction

The EU’s Cyber Resilience Act, that is, Regulation (EU) 2024/2847, was agreed upon in October 2024. The paper presents an analysis of the CRA’s implications for vulnerability coordination, including vulnerability disclosure. Although the handling of vulnerabilities is a classical research topic, the CRA imposes some new requirements that warrant attention. It also enlarges the scope of theoretical concepts involved. For these reasons, the paper carries both practical relevance and timeliness. Regarding timeliness, the reporting obligations upon severe incidents and actively exploited vulnerabilities will be enforced already from September 2026 onwards. Regarding practical relevance, it is worth elaborating and clarifying the obligations and concepts involved because some vendors have had difficulties with them due to a lack of expertise and other reasons [1]. In terms of explicitly related work, the paper continues the initial assessments [2] that were conducted based on the European Commission’s proposal for the CRA. By using conceptual analysis [3], the research question examined is: what new requirements the CRA entails for vulnerability coordination? To the best of the authors’ knowledge, the question has not been previously asked and answered.

The CRA is a part of a larger regulatory package for cyber security that was pursued by the von der Leyen’s first Commission, which was in office between 2019 and 2024. Although many of the other regulations and directives in the package are on the side of critical infrastructure, the overall goal of improved coordination, which can be understood broadly as a management of dependencies [4, 5], is strongly present throughout the package. Whether it is risk analysis or incident management, the EU context generally implies that some coordination is required at multiple levels; between cyber security professionals, companies, industry sectors, national public authorities, and EU-level institutions, among other abstraction levels [6]. To make sense of the coordination involved, it is useful to analytically separate horizontal coordination (such as between the member states) and vertical coordination, which occurs between EU-level institutions and units at a national level [7, 8]. Then, as will be elaborated, the CRA involves both horizontal and vertical coordination. Coordination also requires technical infrastructures.

Regarding the larger regulatory package for cyber security, relevant to mention is Directive (EU) 2022/2555, which is commonly known as the second network and information systems (NIS2) security directive. With respect to vulnerability coordination – a term soon elaborated in Section 2, the directive strengthens and harmonises the role of national computer security incident response teams (CSIRTs) in Europe. In general, various networks between CSIRTs, in both Europe and globally, have been important for improving cyber security throughout the world, often overcoming obstacles that more politically oriented cyber security actors have had [9]. Importantly for the present purposes, the NIS2 directive, in its Article 12(2), specifies also an establishment of a new European vulnerability database operated by the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA), which is the principal EU-level institution coordinating particularly with the national CSIRTs but also involved in international collaboration. Although the database is already online [10], it is still too early to say with confidence whether the CRA and NIS2 may affect the infrastructures for vulnerability archiving, which is currently strongly built upon institutions and companies in the United States, including particularly the not-for-profit MITRE corporation involved in the assignment of Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVEs) and the National Vulnerability Database (NVD) maintained by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) of the United States.

With respect to the EU’s regulatory cyber security package, it can be further noted that the CRA is rather unique in a sense that its legal background and logic are motivated by the EU’s product safety law and the general consumer protection jurisprudence [2]. Therefore, also the associated terminology is somewhat different, compared to the other legislative acts in the package. For instance, the CRA brings market surveillance authorities to the public administration of cyber security in the EU. In general, these authorities are responsible for ensuring that only compliant products enter into and circulate on the EU’s internal market; the examples include authorities ensuring the safety of food, drugs, aviation, chemicals, and so forth.

The CRA covers the whole information technology sector and beyond. Both hardware and software products with a networking functionality are in its scope. Among the notable exemptions not covered by the regulation, as specified in the CRA’s Article 2, are medical devices, motor vehicles, and ships and marine equipment. Furthermore, recital 12 clarifies that cloud computing is also excluded. The CRA categorises products into three categories: ‘‘normal’, ‘‘important’, and ‘‘critical’ products. While all products need to comply with the CRA’s essential requirements, which have been analysed in recent research [11, 12], more obligations are placed upon the important and critical products. However, in what follows, the focus is only on the CRA’s implications for vulnerability coordination, including vulnerability disclosure. With this focus in mind, Section 2 introduces the vulnerability coordination and disclosure concepts. Then, the subsequent Section 3 discusses and elaborates the CRA’s new implications to vulnerability coordination and disclosure. The implications are not uniform across everyone; therefore, Section 4 continues by briefly elaborating the requirements for open source software (OSS) products and their projects. To some extent, the CRA addresses also the pressing issues with supply chain security. The important supply chain topic is discussed in Section 5. A conclusion is presented in Section 6. The final Section 7 discusses further research.

2. Vulnerability Disclosure and Coordination

There are various ways to disclose and coordinate a vulnerability between the vulnerability’s discoverer and a software vendor affected by the vulnerability. Historically – and perhaps still so – a common practice was a so-called direct disclosure through which a discoverer and a vendor coordinate and negotiate privately, possibly without notifying any further parties, including maintainers of vulnerability databases and public authorities [13]. Partially due to the problems associated with direct disclosure, another historical – and sometimes still practiced – process was a so-called full disclosure via which a discoverer makes his or her vulnerability discovery public, possibly even without notifying a vendor affected or anyone else beforehand. One of the primary reasons for the full disclosure practice was – and sometimes still is – a deterrence against vendors who would not otherwise cooperate [13, 14]. However, this practice can be seen to increase security risks because sensitive information is publicly available but no one has had time to react; there are no patches available because a vendor may not even know about a vulnerability information being available in the public.

For this reason and other associated reasons, a third vulnerability disclosure model emerged. It is called coordinated vulnerability disclosure; in essence, a discoverer contacts an intermediary party who helps with the coordination and collaboration with a vendor affected, often also providing advices to other parties and the general public through security advisories and security awareness campaigns. This coordinated disclosure model is the de facto vulnerability disclosure practice today. Regarding the intermediaries involved, a national CSIRT is typically acting as a coordinator, but also commercial companies may act in a similar role, as is typical in the nowadays popular so-called bug bounties and their online platforms. In addition to security improvements, commercial bug bounty platforms may give vendors more control over disclosure processes [15], while for discoverers they offer monetary rewards, learning opportunities, and some legal safeguards [16]. It is also important to emphasise that today practically all coordinated vulnerability disclosure models further follow a so-called responsible disclosure, meaning that vendors are given a fixed period to develop and release patches before information is released to the public.

With respect to Europe and the CSIRT-based coordinated vulnerability disclosure model, the NIS2 directive specifies in its Article 12(1) three primary tasks for the national CSIRTs in the member states: (1) they should identify and contact all entities concerned, including the vendors affected in particular; (2) they should assist natural or legal persons who report vulnerabilities; and (3) they should negotiate disclosure timelines and arrange coordination for vulnerabilities that affect multiple entities. While simple, these legal mandates for public sector bodies are important because the legal landscape for vulnerability disclosure has been highly fragmented in Europe [17, 18]. The CRA relies partially upon these mandates in NIS2, but it also imposes new requirements for both national CSIRTs and vendors.

Before continuing further, it should be clarified that a broader term of vulnerability coordination has sometimes been preferred in the literature because vulnerability disclosure presents only a narrow perspective on the overall handling of vulnerabilities [5]. In addition to contacting, communicating, assisting, and negotiating, numerous other tasks are typically involved, including development of patches, testing these, and delivering these to customers, clients, and users in general, assignment of CVE identifiers, writing and releasing security advisories, archiving information to vulnerability databases, and so forth and so on. These additional tasks do not affect only vendors; also, CSIRTs may need to carry out additional tasks beyond those specified in NIS2. For these reasons, also the present work uses the vulnerability coordination term.

3. The CRA’s Vulnerability Coordination Requirements

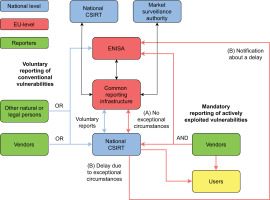

The CRA separates voluntary vulnerability disclosure from mandatory obligations placed upon vendors. Regardless whether a disclosure of a vulnerability is done on voluntary or mandatory basis, it should be primarily done through a national CSIRT, although voluntary disclosure may be done also to ENISA directly according to the CRA’s Article 15(1). Then, according to Article 15(2), both vendors and others may also report not only vulnerabilities but also severe security incidents and so-called near misses. These near misses are defined in the NIS2’s Article 6(5) as events that ‘could have compromised the availability, authenticity, integrity, or confidentiality of stored, transmitted, or processed data or of the services offered by, or accessible via, network and information systems’ but which were successfully mitigated. These mitigated security events are one but not the only example of new terminology brought by the EU’s new cyber security law.

When a disclosure is done to a national CSIRT, the given CSIRT should then without undue delay carry out vertical coordination towards the EU-level. This important obligation placed upon national public sector authorities is specified in the CRA’s Article 16(1), according to which a common EU-level disclosure infrastructure is established. It is maintained by ENISA. Through this infrastructure, according to Article 16(2), a given national CSIRT should notify other European CSIRTs designed as public sector authorities on those territories on which a vendor’s vulnerable products have been made available.

The territorial notion seems sensible enough when dealing with physical products, whether routers, mobile phones, or automobiles. However, many digital products, including software products in particular, are distributed online without any specific territorial scope. For such products, it seems a reasonable assumption that all European CSIRTs should be notified. This point applies particularly to large software vendors. Similar reasoning was behind a schism during the CRA’s political negotiations because some companies and member states feared that sensitive vulnerability information would unnecessarily spill over throughout Europe due to the EU-level reporting infrastructure [8]. The schism was resolved by relaxing the obligation placed upon CSIRTs.

In particular, according to Article 16(2), national CSIRTs may delay coordination and reporting towards the EU level under exceptional circumstances requested by a vendor affected. The article specifies three clarifying conditions regarding these exceptional circumstances: (1) a given vulnerability is actively exploited by a malicious actor and no other member state is affected; (2) immediate reporting would affect the essential interests of a member state; and (3) imminent high cyber security risk is stemming from reporting. Although a national CSIRT should always still notify ENISA about its decision to delay reporting, it seems that the three conditions are so loose that most cases could be delayed in principle. Time will tell how the regulators interpret the exceptional circumstances in practice.

When no exceptional circumstances are present and reporting is done normally by a CSIRT, it should be clarified that both vertical and horizontal coordination is present. A CSIRT’s notification towards the EU level is vertical in its nature, while distributing information to other CSIRTs is a horizontal activity. In addition, further horizontal coordination is present because the CRA’s Article 16(3) specifies that a CSIRT should also notify any or all market surveillance authorities involved. This obligation complicates the coordination substantially because it may be that numerous market surveillance authorities are present, including everything from product safety authorities to customs. Alternatively, it may be that a member state has specified its national CSIRT also as a market surveillance authority in the CRA’s context. Again, time will tell how the coordination works in practice. Future evaluation work is required later in this regard.

The exceptional circumstances noted contain the concept of actively exploited vulnerabilities. Such vulnerabilities are a core part of the CRA. An actively exploited vulnerability is defined in Article 3(42) as ‘a vulnerability for which there is reliable evidence that a malicious actor has exploited it in a system without permission of the system owner’. Recital 68 clarifies that security breaches, including data breaches affecting natural persons, are a typical example. The recital also notes that the concept excludes good faith testing, investigation, correction, or disclosure insofar as no malicious motives have been involved.

Then, according to Article 14(1), all vendors should notify about actively exploited vulnerabilities in their products to both a given national CSIRT and ENISA. Article 14(2) continues by specifying that vendors should deliver an early notification within 24 hours, an update within 72 hours, and a final report within 2 weeks. As could be expected, concerns have been expressed among vendors about these strict deadlines [1]. Also, reporting quality remains a question mark [6]. In any case, the subsequent paragraphs 3 and 4 in Article 14 obligate vendors to report not only about actively exploited vulnerabilities but also about severe security incidents. These are defined in the NIS2’s Article 6(6) analogously to the near misses but without the successful mitigation condition. Furthermore, Article 14(8) specifies that both actively exploited vulnerabilities and severe security incidents should be communicated to the users impacted, possibly including the general public, either by a vendor affected or a given CSIRT.

Regarding vulnerabilities, as can be seen also from Fig. 1, it should be underlined that the mandatory notifications only involve actively exploited vulnerabilities. Thus, among other things, so-called silent patching is excluded from the CRA’s scope; it refers to cases in which a vendor has found a vulnerability from its product and silently corrected it without making the information available to others [13]. A more important point is that the definition for actively exploited vulnerabilities is rather loose. When considering a possibility of underreporting – a topic that has been discussed in the literature in somewhat similar settings [19], particularly the wording about reliable evidence raises a concern. A relevant question is: whose evidence? If vendors alone answer to the question, underreporting may occur. Though, other parties too, including public authorities, have threat intelligence platforms, security information and event management (SIEM) systems, and many related techniques deployed. Against this backdrop, a vendor deciding not to report an actively exploited vulnerability may later on find itself as having been non-compliant. In addition, Article 60 allows market surveillance authorities to conduct sweeps to check compliance.

It is important to further note that the concept of actively exploited vulnerabilities is used implicitly also in the United States. In particular, the Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Agency (CISA) therein maintains a catalogue of known exploited vulnerabilities (KEVs) [20]. Given the ENISA’s and CISA’s established cooperation [21], it remains to be seen whether the catalogue will be used also for enforcing the CRA or otherwise helping its implementation. An analogous point applies to the international coordination between vulnerability databases, including particularly between the NVD and the EU’s new vulnerability database. A related important point is that less strict vulnerability reporting requirements are imposed upon OSS projects and their supporting foundations, which are known as stewards in the CRA’s parlance.

Regarding KEVs, the available documentation [20] says that three conditions must be satisfied for a vulnerability to be a KEV. First, a KEV must have a CVEs identifier assigned. Then, exploitability is understood along the lines of the Common Vulnerability Scoring System (CVSS) as the ease of an attacker to take advantage of a CVE-referenced vulnerability. Thus, exploitability varies according to a number of factors, such as whether a vulnerability can be exploited remotely through a network, whether a proof-of-concept exploit is available, whether authentication or privileges are required for exploitation, and so forth and so on. A vulnerability that cannot be exploited under reasonable constraints cannot be a KEV. Second, however, for an exploitable vulnerability to be a KEV, it must have been either exploited or under active exploitation. Both terms require that there is ‘reliable evidence that execution of malicious code’ has occurred [20]. Such evidence does not necessarily mean that a vulnerability has been exploited successfully; a KEV can refer also to an attempted exploitation, including those conducted in a honeypot or related deception environment. It can be also noted that execution of malicious code rules out network scanning and denial of service attacks. Third, a KEV must have clear remediation guidelines for it to be accepted into the catalogue. These range from updates provided by vendors to temporary mitigations and workarounds. It will be interesting to see whether also the CRA’s concept of actively exploited vulnerabilities will be tied to these or closely related principles or whether a new European conceptual framework will be developed in the future.

Finally, it is important to emphasise that the CRA’s so-called essential cyber security requirements, which, like with the EU’s product safety law [7], will be accompanied with harmonised standards, contain also obligations explicitly related to vulnerabilities and their coordination. In general, as specified in Annex I, vendors should only make available products without known exploitable vulnerabilities, but they should also ensure that vulnerabilities can be addressed through security updates, including, where applicable, automated security updates separated from functional updates that bring new features [12]. They must also establish and enforce a coordinated vulnerability disclosure policy, and apply effective and regular security testing and reviews, among other things. As discussed in Section 5, the essential cyber security requirements imply also new requirements for supply chain management.

4. The CRA’s Vulnerability Coordination Requirements for Open Source Projects

Many OSS projects and their foundations were critical about the CRA during its policy-making. Some notable OSS foundations even raised an argument that online distribution of OSS might be blocked in the EU due to the CRA (see [22], among many others during the CRA’s policy-making). While the argument might have merely been a part of an aggressive lobbying strategy, some have used a term ‘regulatory anger’ to describe the situation during the political negotiations, concluding that the new regulatory obligations for OSS projects are modest at best and relatively easy to fulfill [23]. The reason for the only modest implications originates from the fact that the CRA essentially only applies to commercial OSS projects. This restriction is clarified in recitals 17, 18, and 19. These recitals clarify that natural or legal persons who merely contribute to OSS projects are not within the regulation’s scope. Nor is a mere distribution of OSS in the CRA’s scope. Instead, the keyword is monetisation.

To quote from recital 19, the CRA only applies to OSS projects that are ultimately intended for commercial activities’, including ‘cases where manufacturers that integrate a component into their own products with digital elements either contribute to the development of that component in a regular manner or provide regular financial assistance to ensure the continuity of a software product.This clarification essentially means that the main target is OSS foundations; the Linux Foundation would be the prime example. However, none of the keywords – including monetisation, ultimate intentions, regular contributions, and financial assistance – are actually defined in Article 3. This lack of definitions makes it unclear how the regulators and legal systems will interpret the situation. Regardless, even with vague definitions and potential disputes, the actual regulatory mandates placed upon OSS foundations are only light.

Thus, Article 24 specifies three obligations for OSS foundations: (1) they are obliged to develop and publish cyber security policies that address particularly the coordination of vulnerabilities and foster the voluntary reporting of vulnerabilities; (2) they must cooperate with market surveillance authorities who may also request the cyber security policies; and (3) they too must report about actively exploited vulnerabilities and severe security incidents. While the first two obligations are mostly about documentation, and most large OSS foundations likely already have such documented policies in place, the reporting obligation may perhaps be somewhat difficult to fulfill because the supporting OSS foundations are mostly involved in the development – and not deployment – of OSS. This point reiterates the earlier remark about reliable evidence. However, according to Article 64(10)(b), OSS foundations are excluded from the scope of administrative fines. This exclusion casts a small doubt over whether the supervising authorities have a sufficient deterrence against non-compliance.

It can be mentioned that the initial legislative proposal for the CRA, identified as COM/2022/454 final, was more stringent about OSS. Thus, perhaps the lobbying by OSS stakeholders was also successful. Having said that, there are two important points that many OSS lobbyists missed during the negotiations. The first is that the CRA’s Article 25 entails a development of voluntary security attestation programmes for OSS projects to ensure compliance with the essential cyber security requirements. Such programmes can be interpreted to boost the security of OSS [23]. The second point stems from Article 13(6), which mandates that a vendor who discovers a vulnerability from a third-party software component, including an OSS component, must report the vulnerability to the natural or legal persons responsible for the component’s development or maintenance. Also, this reporting obligation can be seen to improve the security of OSS too. It is also directly related to supply chains.

5. The CRA and Supply Chains

Both the CRA and NIS2 directive address supply chain security, either explicitly or implicitly. In fact, throughout the CRA’s motivating 130 recitals, supply chain security is frequently mentioned. Many of the new supply chain obligations are specified in Annex I. Accordingly, vendors should try to identify and document vulnerabilities in third-party software components they use; for this task, they are mandated to draw up a software bill of materials (SBOM) for their products.

A SBOM is defined in Article 3(39) to mean ‘a formal record containing details and supply chain relationships of components included in the software elements of a product with digital elements’. In practice, SBOMs are primarily about software dependencies, whether managed through a package manager or bundled into a software product directly. These are also under active research [24, 25]. As motivated by the CRA’s recital 77, SBOMs are seen not only important for regulatory purposes but they are also perceived as relevant for those who purchase and operate software products. However, the same recital notes that vendors are not obliged to make SBOMs public, although they must supply these to market surveillance authorities upon request according to Article 13(25). Confidentiality must be honoured in such cases.

Yet, SBOMs are not the only new obligation related to supply chains. Historically, there was a problem for many vulnerability discoverers to find appropriate contact details about organisations and their natural persons responsible [13]. The problem and related obstacles likely still persist today, as hinted by experiences with large-scale coordinated vulnerability disclosure and the poor adoption rate of new initiatives, such as the so-called security.txt for the World Wide Web [26–28]. To this end, paragraph 6 in Annex I mandates vendors to also provide contact details for reporting vulnerabilities. This obligation is important also for regulators; as was noted in Section 2, they should coordinate vulnerability handling, including disclosure, also in case multiple parties are involved. Without knowing whom to contact, let alone which components have been integrated, such multi-party coordination is practically impossible. The same point applies to the earlier note about obligations placed upon vendors who may discover vulnerabilities in third-party components they use. The obligation to provide contact details is recapitulated in paragraph 2 of Annex II.

6. Conclusion

The paper examined, elaborated, and discussed the implications from the EU’s new CRA regulation upon vulnerability coordination. When keeping in mind the paper’s framing only to vulnerability coordination, the CRA’s new obligations cannot be argued to be substantial – in fact, it can be argued that many of these obligations have already long belonged to security toolboxes of responsible vendors prioritising cyber and software security. Nevertheless, (1) among the new legal obligations are mandatory reporting of actively exploited vulnerabilities and severe cyber security incidents for which (2) strict reporting deadlines are also imposed. On the public administration side, (3) the CRA strengthens the EU-level administration due to ENISA’s involvement and the establishment of a common European reporting infrastructure, including a new European vulnerability database. In addition, (4) administrative complexity is also increased due to the involvement of new public sector bodies, including market surveillance authorities in particular. Furthermore, (5) the new mandatory reporting obligations apply also to OSS foundations with commercial ties, but also commercial vendors must report vulnerabilities to OSS projects whose software they use. Finally, (6) the CRA imposes new requirements also for supply chain management, some of which are related to vulnerability coordination; the notable examples are mandates to roll out SBOMs and provide contact details.

7. Further Work

Of the new regulatory obligations and points raised thereto, further research is required about the concept of actively exploited vulnerabilities. Such research might also generally reveal whether the existing empirical vulnerability research has been biased in a sense that serious vulnerabilities affecting actual deployments have perhaps been downplayed; with some notable exceptions [29], the focus has often been on reported vulnerabilities affecting software products, components, and vendors, not on their actual deployments [30]. Another related topic worth examining is the theoretical and practical relation between KEVs and the CRA’s notion of actively exploited vulnerabilities.

On a more theoretical side of research, further contributions are required also regarding the other fundamental concepts involved. Regarding the exploitation theme, many further concepts have been introduced in recent research, among them a concept of likely exploited vulnerabilities [31]. A conceptual enlargement applies also to security incidents. Although attempts have been made to better understand and theorise how different incident types are related to each other in terms of EU law [6], it still remains generally unclear what exactly separates a severe incident from a ‘conventional’, non-severe incident, or a significant incident from a severe incident. These and other related interpretation difficulties can be seen also as a limitation of the current paper.

Then, regarding supply chains, further research is required also on SBOMs. Although technical research is well underway in this regard, including with respect to a question of how to generate SBOMs automatically [32], many questions remain about applicability, usability, and related aspects, including for regulatory purposes. Although perhaps only partially related to the paper’s explicit theme, a relevant research question would also be whether, how, and how well vendors can comply with the requirement to provide security patches, preferably in an automated manner. When recalling the CRA’s scope, the question is non-trivial. While providing automated security updates for Internet of things devices sounds like a reasonable and well-justified goal, the situation may be quite different in industrial settings [12]. It also remains generally unclear whether the CRA applies to physical security, including patching of software operating in air-gapped and related deployments. As always, further policy-oriented research is also needed. Among other things, a close eye is needed to monitor and evaluate the regulation’s future implementation, adoption, administration, and enforcement.

Regarding the CRA’s future implementation, a particularly relevant research topic involves examining the upcoming harmonised standards upon which the essential cyber security requirements are based. This topic is important already because complying with these standards provides a presumption of conformity according to the CRA’s Article 27(1). The topic can be extended to other conformity assessment procedures involved, including the mandatory third-party audits required for critical products and the CRA’s relation to the older cyber security certification schemes in the EU. Among other things, a good topic to examine would be the accreditation of conformity assessment bodies. It may be that the CRA will also entail a new labour market demand for cyber security professionals specialised into security testing, auditing, and related domains. At the same time, as also implicitly remarked in the CRA’s Article 10, there is allegedly a cyber security skill gap in Europe and elsewhere [33]. As the gap may correlate with education [34, 35], it may also be worthwhile to further study the CRA and its future implementation with education and curricula in mind. Regarding adoption, it is relevant to know which conformity assessment procedures vendors will prefer in the future; according to Article 32(1), there are four distinct procedures for conformity assessments under the CRA.

Although it is too early to speculate what the CRA’s broader implications may be, three general points can be still raised. First, the larger regulatory cyber security package in the EU has expectedly raised some criticism that fragmentation and complexity have increased [8, 36]. The CRA has contributed to this increase. The CRA also interacts with the EU’s other legal cyber security acts. In particular, as the NIS2 directive also imposes reporting obligations for vendors, synchronisation between the CRA and NIS2 has been perceived as crucial [2]. Second, a notable limitation of the CRA is that it offers no legal guards against criminal or civil liability from disclosing vulnerabilities. Such guards have often been seen important in the literature [16, 17]. Third, it remains to be seen whether the CRA actually improves the cyber security of products. Although all points require further research, including rigorous evaluations, particularly the last point is fundamental in terms of the CRA’s explicit goals. According to the Act’s first recital, cyber insecurity affects not only the EU’s economy but also its democracy as well as the safety and health of consumers. Already against this backdrop, it is important and relevant to evaluate in the future how well the CRA managed to remove or at least mitigate cyber insecurity in the EU.