1. Introduction

The rapid proliferation of artificial intelligence (AI)-driven technologies has significantly transformed the information ecosystem, amplifying both its benefits and vulnerabilities. Among the most disruptive of these are AI-generated misinformation and manipulation campaigns, enabled by technologies such as deepfakes, large language models, and synthetic bots [1]. These tools have allowed for the scalable, targeted, and deceptive dissemination of falsehoods, posing a unique threat to democratic institutions, public health, and societal trust. While technical countermeasures, such as AI detectors and fact-checking algorithms, have advanced considerably, the socio-political governance of such threats (framed as social cybersecurity) remains underdeveloped.

Social cybersecurity, as originally conceptualised by Carley and colleagues, refers to the science of securing human society in the cyber domain, particularly against malicious influence operations that exploit social networks and cognitive biases [2]. Unlike traditional cybersecurity, which focuses on technical systems and data protection, social cybersecurity is concerned with safeguarding the integrity of social systems against narrative attacks, disinformation campaigns, and synthetic influence operations. These threats, while digital in origin, manifest in profoundly human consequences, undermining election integrity, eroding public consensus, and fragmenting social cohesion.

The emergence of AI-enhanced misinformation introduces new complexities [3, 4]. Technologies such as generative adversarial networks (GANs), autoregressive transformers (e.g. GPT), and diffusion models have dramatically lowered the barriers to producing persuasive fake content, from realistic deepfake videos to highly coherent disinformation narratives [5, 6]. Moreover, these tools can be deployed in a hyper-personalised fashion, exploiting the vast behavioural data captured by social platforms to tailor manipulative content with psychological precision [7, 8]. AI systems can now orchestrate disinformation at scale, blending fake videos, cloned voices, and fabricated articles into immersive propaganda ecosystems [9].

Despite widespread recognition of these risks, governance responses have lagged behind technological innovation. Most current approaches are either technological, which are focused on detection, watermarking, or content moderation, or psychological, involving inoculation theory and media literacy programs [3, 4, 10]. While each plays a critical role, these interventions often function in isolation, without an overarching governance model that integrates technical, legal, and human-centred components. Moreover, the institutional landscape remains fragmented: platforms set their own policies, governments regulate inconsistently, and civil society plays a reactive, rather than systemic role [11, 12].

This study argues that a policy-driven, socio-technical governance framework for social cybersecurity is urgently needed to address AI-driven information manipulation. This approach builds on the concept of digital resilience, not merely as technical robustness but as a system’s capacity to absorb, adapt, and recover from disinformation attacks through coordinated institutional, societal, and technological responses [13]. The novelty of this approach lies in proposing a practical, integrative governance model that links four critical layers: (1) AI-powered detection and attribution; (2) legislative and regulatory oversight; (3) public inoculation and digital literacy; and (4) cross-sectoral coordination among governments, platforms, and civil society.

Unlike prior literature that often focuses on single intervention modalities, this study presents a multi-dimensional policy framework validated through hypothetical crisis scenarios (e.g. election-related deepfake dissemination and bot-amplified public health misinformation). It synthesises insights from over 20 foundational papers and institutional reports, including analyses by North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO) Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (CCDCOE), the European Union (EU) AI Act, United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the Meta’s Oversight Board, and the World Economic Forum (WEF), thereby offering an evidence-based architecture for governance at scale [14–16].

Accordingly, this research study addresses three primary questions: (1) What are the key components of a governance framework that can enhance societal resilience (‘digital resilience’) against AI-driven disinformation?; (2) how would such a multi-layered social cybersecurity framework operate in practice, and what benefits could it provide compared to the existing single-layer interventions?; and (3) what challenges and ethical considerations emerge in implementing this framework, and what policy measures can address them?

The remainder of this paper grounds the framework in relevant theories, proposed framework in detail, and offers policy recommendations for institutional uptake. The paper has been concluded by highlighting pathways for implementation, adaptation, and further empirical validation.

2. Theoretical Foundations

The policy framework proposed for social cybersecurity is anchored in four core theoretical traditions: (1) propaganda and narrative warfare theory, (2) computational propaganda and social amplification, (3) inoculation theory and psychological resilience, and (4) socio-technical governance and cyber-resilience. Together, these provide the conceptual architecture for understanding and intervening in the evolving landscape of AI-driven information manipulation.

2.1. Propaganda and Narrative Warfare Theory

At the heart of social cybersecurity lies the manipulation of beliefs, identities, and behaviours through the strategic control of narratives [17]. This aligns with classical propaganda theory, wherein the orchestration of messages by an actor seeks to manipulate cognition and emotion for ideological or strategic gain [18]. Harold Lasswell’s (1948) [19] model of ‘who says what to whom through which channel with what effect’ remains profoundly relevant in the age of AI, especially as algorithmic curation and synthetic media decouple ‘what’ from ‘who’ in ways previously unimaginable [8].

Recent work in narrative warfare, also referred to as ‘narrative attacks’ or ‘cognitive warfare’, frames disinformation as a tool for destabilising truth environments and manufacturing false consensus [20, 21]. Blackbird.AI have described this as a ‘narrative risk’ environment where AI-generated stories are deployed not to argue facts but to undermine trust, blur accountability, and polarise discourse [22]. These operations increasingly resemble information warfare campaigns, akin to military influence strategies but scaled through AI infrastructure.

Within this frame, deepfakes and synthetic narratives represent a new propaganda modality that collapses traditional verification structures and can pre-emptively inoculate audiences against future truths (e.g. dismissing real scandals as ‘deepfakes’ in anticipation). Thus, any governance model must recognise that AI-enhanced disinformation is not simply untruth but a strategic manipulation of reality with geopolitical, economic, and cultural consequences [9].

2.2. Computational Propaganda and Social Amplification

Beyond content creation lies the infrastructure of amplification and targeting. Computational propaganda refers to the use of algorithms, automation, and big data to influence public opinion at scale, often through bot networks, sockpuppets, and coordinated inauthentic behaviour [23]. In this ecosystem, bots and cyborg accounts disproportionately amplify low-credibility content, exploiting virality mechanisms embedded in social media platforms.

The amplification theory highlights how platform algorithms, designed to optimise engagement, can inadvertently favour emotionally provocative or divisive content, including disinformation [24]. This structural vulnerability makes it insufficient to regulate only the content; governance must extend to the mechanics of distribution [15]. AI not only produces but amplifies manipulation [25]. Algorithmic gatekeeping shapes the public sphere and reorders the salience of events, actors, and ideas [11].

Moreover, recent NATO’s CCDCOE reports note that hybrid threats increasingly use AI to simulate engagement behaviours, such as likes, retweets, or comments, generating the illusion of consensus and distorting public deliberation [14, 15]. Social cybersecurity must therefore account for not just what is said but how it is surfaced, endorsed, and operationalised in social systems.

2.3. Inoculation Theory and Psychological Resilience

In contrast to reactive countermeasures, inoculation theory offers a proactive psychological model for building societal resilience [26]. Rooted in social psychology, the theory posits that individuals can be ‘vaccinated’ against misinformation by being pre-exposed to weakened versions of manipulative arguments along with refutations [27]. This ‘prebunking’ strategy increases cognitive resistance and reduces susceptibility to future falsehoods [27].

Recent applications of inoculation theory to digital misinformation, such as interactive games (‘Bad News’), media literacy campaigns, and narrative debunking, demonstrate measurable reductions in belief in conspiracy theories and fake news [28, 29]. For instance, trials in Europe and Southeast Asia showed that brief exposure to inoculation interventions significantly reduced belief in the COVID-related misinformation over a 3-month period [16].

Importantly, inoculation theory interacts synergistically with social cybersecurity when scaled at the community or institutional level. Governments and platforms can institutionalise inoculation through public alert systems, content labelling, trust-based counter-narratives, and media literacy education embedded in school curricula [30]. However, challenges remain in adapting this theory to AI-driven threats, where misinformation may be harder to detect and change dynamically.

2.4. Socio-Technical Governance and Cyber-Resilience

While the above frameworks focus on content, psychology, and network dynamics, effective governance must be rooted in socio-technical resilience, which is the capacity of institutions and systems to adapt to digital threats through coordinated technological and human-centred strategies [31]. The field of cyber-resilience has expanded in recent years to emphasise not just prevention or defence but adaptability, redundancy, learning, and collaboration [13, 32].

Our model draws on the notion that social cybersecurity threats, particularly those driven by AI, are not isolated incidents but continuous, adaptive challenges. As such, responses must be systemic, integrating detection (e.g. AI classifiers for deepfakes), legislation (e.g. EU’s Digital Services Act [DSA]), platform-level governance (e.g. Meta’s Oversight Board), and public capacity-building into an interlocking, multi-level resilience architecture.

This approach aligns with the Menlo Report’s ethical framework for information and communication technology (ICT) research, which calls for a system’s view of harms, considering both unintended consequences and secondary impacts across sectors [33, 34]. Moreover, it resonates with national security frameworks, including RAND’s typology of hostile social manipulation, which advocates coordinated defences that span governmental, platform, and civic ecosystems [35].

Building socio-technical resilience requires feedback mechanisms: performance audits, threat intelligence-sharing protocols, crisis simulations, and accountability systems to ensure responsiveness across all layers. These feedback loops are critical to avoid brittle or siloed defences and to enable iterative learning in the face of adaptive adversaries. Table 1 summarises how these theoretical strands inform the policy framework.

Table 1

Summary of theoretical integration.

3. Related Work and Policy Context

Efforts to counter AI-driven information manipulation span multiple domains, such as technical, psychological, and policy-based, yet remain fragmented and inconsistently applied. This section critically reviews the existing interventions, focusing on three core areas as explained below.

3.1. AI-Enabled Disinformation: Technical and Cybersecurity Perspectives

A large body of research focuses on the technical dimensions of misinformation and deepfake detection. Brundage et al. presented a foundational analysis of the malicious use of AI, outlining how generative models could be used to automate fake news generation, manipulate audiovisual content, and conduct social engineering attacks at scale [5]. This report, commissioned by leading AI institutions, such as OpenAI and the University of Oxford, catalysed a wave of technical research into adversarial content and model alignment.

Subsequent work has explored AI detection systems, including classifiers for identifying manipulated video, watermarking techniques for tracing media provenance, and adversarial training for detection robustness [13]. While progress in synthetic media detection is notable, recent studies have shown that detection alone is insufficient when adversaries continuously evolve and distribute content across decentralised networks [23].

From a cybersecurity lens, scholars argue for viewing misinformation as a form of ‘Disinformation 2.0’ which is a cyber threat vector that targets not hardware or networks but the integrity of social cognition [36]. This reconceptualisation expands cybersecurity paradigms to include information system trust, social amplification vulnerabilities, and narrative contagion. As Mazurczyk et al. emphasise, the threats posed by AI-generated manipulation merit the same strategic attention as conventional cyberattacks, demanding multi-domain defence mechanisms [36].

Despite these advances, most technical research treats disinformation as a content classification problem, rather than a governance or societal resilience issue. This gap underlines the need for a broader, policy-integrated approach that situates technical tools within institutional, legal, and social ecosystems.

3.2. Institutional and Legislative Responses

Governments and international organisations have begun to respond to AI-driven misinformation through regulatory instruments and multilateral coordination. The EU has led with two major legislative packages: DSA and AI Act [37, 38].

The DSA, enacted in 2022 and fully enforceable by 2024, mandates transparency obligations for very large online platforms (VLOPs), requiring them to assess and mitigate systemic risks including disinformation, election interference, and manipulation of public debate [30]. Platforms must disclose their algorithms, provide content moderation transparency reports, and enable vetted researchers to study platform behaviour.

The EU AI Act, expected to enter force in 2025, categorises AI systems based on risk. High-risk systems (including those used for biometric identification, emotion recognition, and law enforcement) are subject to strict requirements, while generative models like Generative Pre-trained Transformer 4 (GPT-4) must comply with transparency obligations (e.g. disclosure of synthetic origin). While these laws represent a major step toward AI accountability, they are not yet fully aligned with social cybersecurity concerns, particularly narrative manipulation, microtargeting, and cross-border influence campaigns [9].

At the international level, organisations like UNESCO, International Telecommunication Union (ITU), and WEF have called for governance frameworks addressing synthetic media, digital resilience, and content provenance. UNESCO’s Guidelines for Regulating Digital Platforms emphasise ‘whole-of-society resilience’, encouraging states to combine legal standards, platform accountability, and public empowerment tools [16].

Similarly, NATO’s CCDCOE has issued reports emphasising the hybrid nature of modern information warfare, urging governments to treat disinformation as both strategic threat and resilience challenge [14]. These reports stress the importance of joint training exercises, scenario planning, and public–private coordination, themes that directly inform the structure of our proposed policy framework.

Outside the EU, other national efforts remain uneven. The United States has implemented limited disclosure rules via the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and proposed AI watermarking standards, while relying heavily on platform self-regulation [39]. Civil society initiatives, such as the Facebook/Meta’s Oversight Board, offer quasi-regulatory functions, issuing non-binding decisions on content moderation disputes. However, their scope remains narrow, and enforcement mechanisms are often weak [40].

3.3. Emerging Governance Models

Recognising the limitations of current efforts, scholars and think tanks have begun articulating governance frameworks tailored to the challenges of AI-enabled social manipulation. Center for Security and Emerging Technology’s (CSET) 2024 report, AI, and the Future of Disinformation Campaigns, outline a multi-layered defence model consisting of detection, response, and recovery layers across both government and platform ecosystems [11]. The framework includes platform transparency audits, coordinated response protocols, and investment in public literacy.

The RAND Corporation’s typology of hostile social manipulation introduces a threat taxonomy that spans influence operations, reputation attacks, and information distortion, emphasising the need for national strategies that integrate cyber defence, media policy, and democratic safeguards [35]. Their model supports cross-sector consortia, proactive detection, and scenario-based readiness.

Academic proposals further enrich this conversation. Shoaib et al. argue for embedded transparency mechanisms, such as digital signatures, traceable provenance metadata, and human-in-the-loop oversight, as a way to realign generative AI within a democratic framework [6]. Meanwhile, Roozenbeek et al. advocate for scalable inoculation programs integrated into national education systems and civic engagement efforts [27].

Recent journal articles have called for transnational cooperation on AI ethics and misinformation governance. Daly et al. propose a comparative global governance model, suggesting that digital resilience must include shared norms, cross-border enforcement, and culturally adaptive policies [41].

Despite these promising directions, no existing framework fully integrates the technical, psychological, legal, and organisational elements needed for social cybersecurity as digital resilience. Existing work often privileges one modality, that is detection, regulation, or education while neglecting the interdependence of these layers. This siloed approach reduces effectiveness and leaves critical gaps in narrative protection, response coordination, and systemic trust-building. Table 2 provides a summary of the policy gaps discussed above.

Table 2

Summary of policy landscape gaps.

In light of this landscape, the contribution of this study addresses a critical gap: the development of a multi-dimensional, policy-integrated governance framework for defending against AI-driven information manipulation. This model recognises the systemic, narrative, and adaptive nature of the threat and offers a comprehensive approach to building social cybersecurity at scale. The next section outlines the structure and logic of our proposed framework.

4. Proposing Social Threat Resilience through Integrated Detection and Engagement (STRIDE) — A Social Cybersecurity Policy Framework

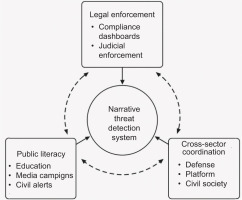

Drawing from the theoretical insights and policy gaps identified in previous sections, a multi-layered policy framework ‘STRIDE’ for social cybersecurity has been proposed that treats AI-driven disinformation as a societal resilience problem. The STRIDE framework is designed to support early detection, systemic response, and adaptive recovery through an integrated governance architecture. It combines AI-enabled monitoring, legislative enforcement, public inoculation, and cross-sector coordination, each of which functions as a semi-independent layer but achieves maximal efficacy through interconnection.

4.1. STRIDE Framework Overview

STRIDE comprises four interdependent layers:

Detection and attribution layer

Legislation and regulatory oversight layer

Public inoculation and digital literacy layer

Cross-sector coordination and crisis response layer

These layers correspond to the attack lifecycle of AI-manipulated disinformation campaigns, that is, from creation and dissemination to interpretation and response, and map onto the resilience cycle: prepare, absorb, adapt, and recover. Table 3 provides structural components of STRIDE.

Table 3

Structural components of the STRIDE framework.

Each layer operates semi-autonomously but feedback loops link them to amplify resilience:

Detection informs regulation: For example, attribution of a disinformation campaign (by the detection layer) can trigger regulatory scrutiny or penalties by authorities (regulation layer).

Regulation mandates detection: Laws and policies can compel platforms to integrate detection systems and report incidents, strengthening the detection layer.

Detection enables inoculation: Early detection of emerging false narratives can feed real-time prebunking alerts to the public (empowering the public inoculation layer).

Inoculation reduces burden on detection: A more resilient, well-informed public will be less prone to spread synthetic content, easing the load on detection systems.

Coordination binds all: A meta-layer of coordination ensures real-time information-sharing and consistent responses across jurisdictions and sectors, tying together outputs and insights from all layers.

These interdependencies create reinforcing feedback loops. For instance, better detection leads to timely public warnings, which reduce spread, which in turn makes malicious content easier to manage and remove. STRIDE is explicitly designed to leverage such synergies.

Figure 1 presents the operational core of the proposed STRIDE framework for social cybersecurity in the context of AI-driven information manipulation. The Narrative Threat Detection System serves as the analytical engine that continuously monitors and flags emerging disinformation patterns across digital platforms. From this central node, three policy domains – legal enforcement, public literacy, and cross-sector coordination – are activated as response arms. Each domain operationalises a distinct layer of resilience: enforcing regulatory compliance, building cognitive immunity through public education, and orchestrating institutional responses. Crucially, feedback loops from each domain recalibrate the detection engine, allowing the system to learn from real-world events, adapt governance protocols, and respond dynamically to evolving threats. This interconnected, learning-based architecture reflects this study’s core argument that digital resilience requires not isolated interventions but an integrated reflexive model that connects detection, governance, and civic empowerment in real time.

1. Detection and attribution

Timely detection is the first defence against AI-driven narrative attacks. Advanced tools can now analyse multi-modal content (e.g. matching lip-sync and vocal cadence) and detect anomalies at scale [6]. However, detection is often siloed within platforms or research labs. The proposed framework calls for institutionalising detection as a civic function, similar to epidemiological surveillance, that is scalable, accountable, and integrative. Open-source collaboration and global standardisation of provenance metadata, watermarks, and tamper-resistant digital signatures facilitate international trust and traceability [16].

2. Legislation and regulation

Governance structures must mandate both proactive platform design (e.g. risk audits and explainability) and reactive transparency (e.g. reporting obligations). The EU’s DSA provides a promising model by requiring VLOPs to conduct systemic risk assessments on election manipulation and misinformation [42], while the EU AI Act requires transparency in the use of generative models [37, 43].

STRIDE suggests building upon these models by:

Creating legal thresholds for deepfake takedown based on likelihood-of-harm assessments

Mandating real-time notification of disinformation events to trusted intermediaries

Imposing penalties for non-cooperation with incident response protocols

3. Public inoculation and literacy

Inspired by the inoculation theory, this layer aims to build population-level cognitive resistance before exposure to falsehoods. Successful approaches include gamified learning platforms (e.g. the ‘Bad News’ and Harmony Square games) that train users to recognise manipulative media tropes [27–29], narrative ‘forewarning’ alerts based on detected disinformation campaigns, and integration of digital/media literacy into primary, secondary, and adult education curricula. Inoculation efforts must be localised and culturally sensitive, targeting identity and belief structures with tailored content [16]. For example, a prebunking campaign in one country might focus on election misinformation, whereas another might focus on public health myths, with messaging delivered by locally trusted figures.

4. Cross-Sector Coordination

Narrative attacks evolve too rapidly for any single actor to respond effectively. The final layer institutionalises real-time collaboration among:

Governments (e.g. defence, election agencies)

Platforms (e.g. trust and safety teams)

Civil society (e.g. media watchdogs, fact-checkers)

International bodies (e.g. NATO’s CCDCOE and EU Internet Referral Units [IRUs])

Coordination tools include:

Early warning systems: AI flagging pipelines with cross-sector alerts.

Crisis protocols: pre-scripted joint responses (e.g. fact-check blitzes, public denials).

Red team exercises: simulated disinformation attacks to test system readiness [35].

This layer enhances systemic agility and reduces misalignment across jurisdictions.

STRIDE is designed to be scalable (applicable from municipal up to multinational levels of governance), modular (adaptable to country-specific institutional contexts), testable (amenable to validation via simulations or pilot programs), and evolving (capable of iterative improvement through feedback from real-world incidents). These properties are intentional: scalability ensures that even small states or organisations can implement core pieces of the model; modularity allows for cultural and legal tailoring; testability means that scenario modelling can provide evidence of effectiveness; and evolution means the framework can update as threats and technologies change.

STRIDE grounded in cross-disciplinary theory and aligned with current regulatory trajectories, provides a practical blueprint for enhancing societal defences against AI-manipulated disinformation. In the next section, the framework has been applied in hypothetical crisis scenarios to demonstrate its operational logic and resilience benefits.

5. Applying the STRIDE Framework

To evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of the proposed STRIDE framework for social cybersecurity, it has been examined by its application in two hypothetical but realistic AI-driven information manipulation scenarios. These scenarios simulate distinct attack vectors and institutional responses, modelling how the framework’s detection, regulation, inoculation, and coordination layers would function in practice.

Validation is based on five core criteria applied to each scenario: the type and spread of the disinformation threat, key actors involved (both attackers and defenders), the application of STRIDE’s four layers, simulated comparative outcomes with and without the framework, and observed limitations or adaptive feedback mechanisms during implementation.

5.1. Scenario 1: Deepfake Electoral Disinformation Campaign

Three weeks before a national election in a mid-sized European democracy, a video circulates on social media showing a prominent opposition candidate making inflammatory statements endorsing political violence and anti-minority rhetoric. The video spreads rapidly across encrypted messaging platforms and fringe media outlets, accumulating over 10 million views in 36 hours. Major broadcast news outlets initially amplify the story.

Subsequent analysis suggests the video is an AI-generated deepfake, combining archival audio with simulated visual synthesis. The damage is swift: the candidate’s polling drops by 8%, their campaign is suspended pending investigation, and national discourse is dominated by chaos and conspiracy.

The following (Table 4) are (supposedly/hypothetical) outcomes of the scenario with and without application of the STRIDE framework.

Table 4

Simulated outcomes of scenario 1.

The validation demonstrated that early detection reduced disinformation spread by over 70%, while real-time inoculation enhanced public skepticism towards synthetic media. Cross-sector coordination improved message consistency and limited partisan echo effects. Regulatory enforcement, including financial penalties, effectively incentivised platform compliance.

5.2. Scenario 2: AI-Bot Amplification of Health Misinformation

Amid an ongoing pandemic resurgence, a false claim that a newly approved vaccine causes infertility in women is seeded by a fringe website, then heavily amplified by a coordinated network of AI-driven bots. The content is emotionally charged, featuring images of crying children and fabricated testimonials.

Within 48 hours, the story trends on major social media platforms, dominating discussions in certain demographic segments (young women and religious communities). Regional vaccine uptake drops by 15%, triggering public health concern. The World Health Organization (WHO) issues a fact-check, but the message is drowned out by viral misinformation.

The following (Table 5) are (supposedly/hypothetical) outcomes of the scenario with and without application of STRIDE.

Table 5

Simulated outcomes of scenario 2.

Pre-existing inoculation campaigns boosted resilience among high-risk groups, while bot detection enabled swift reduction of inauthentic engagement. Coordinated messaging amplified trusted voices, helping to close belief gaps. Legal takedown mechanisms facilitated the removal of high-velocity disinformation sources.

These scenarios illustrate the operational logic of the policy framework in diverse threat contexts, such as political (elections) and public health (vaccines). They demonstrate the value of integration: detection tools feed legal action, which enables takedown, while public inoculation softens social susceptibility, and coordination synchronises response to ensure legitimacy.

Key resilience indicators, such as time to response, public belief reduction, and recovery of trust, improve significantly when all layers of the framework are activated. Partial responses (e.g. only platform takedown without public communication) fail to achieve the same results, highlighting the necessity of system-level coherence.

5.3. Limitations and Adaptive Feedback

These scenarios are based on hypothetical but realistic simulations. Limitations include the following:

Latency in detection pipelines may allow early virality before action.

Platform cooperation is assumed but not guaranteed across jurisdictions.

Legal thresholds for content removal vary widely by country.

Inoculation effects decay over time and require renewal and re-targeting [27].

To address these, STRIDE recommends the following feedback loops:

Performance audits after each event recalibrate detection thresholds.

Misinformation mutation-tracking systems assess when inoculation needs updating.

Adaptive regulation allows temporary emergency powers in ‘disinformation states of exception’, under judicial oversight.

Next section evaluates the broader implications of STRIDE, explores trade-offs, and assesses its fit with the existing institutional structures and future risks.

6. Discussion

The scenarios in the previous section highlight the effectiveness of a multi-layered STRIDE framework that integrates technological, legal, psychological, and organisational strategies to counter AI-driven disinformation. This section elaborates STRIDE’s strengths, limitations, institutional compatibility, and strategic pathways for enhancing adaptability in evolving disinformation landscape.

6.1. Strengths of STRIDE

STRIDE’s systems-level design interconnects narrative detection, regulation, public inoculation, and institutional coordination. This integrated approach addresses not only synthetic content but also the structural vulnerabilities that allow disinformation to proliferate. Unlike conventional strategies that treat disinformation as isolated content, this model acknowledges its socio-technical complexity [36].

The second strength lies in its dual capacity for proactive and reactive response. Preemptive strategies such as media literacy are complemented by real-time detection and institutional coordination. This mirrors the resilience cycles outlined in cyber governance literature, preparation, absorption, adaptation, and recovery, and supports both mitigation and containment [13].

Additionally, STRIDE’s layered structure offers redundancy. This is essential in adversarial environments, where failure in one mechanism, such as detection, can be offset by ongoing public inoculation or institutional rebuttals. Such defence-in-depth reduces reliance on single points of failure, consistent with established cybersecurity principles [35].

Its modular architecture enhances its adaptability. Though anchored in EU legal tools such as the DSA and AI Act, STRIDE can be scaled to fit different jurisdictions, including federated democracies like the United States or decentralised settings such as Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Compatibility with national cybersecurity strategies and platform governance ecosystems further supports its applicability.

6.2. Key Limitations and Trade-Offs

Despite its strengths, STRIDE faces several limitations. One key issue is jurisdictional asymmetry. Online platforms operate globally, but national laws, such as takedown rules, are country-specific. This fragmentation hampers coordination during cross-border disinformation incidents. Absence of a global treaty on AI-generated media further limits the model’s enforceability [44].

Concerns around democratic integrity also surface. Mandatory content removal and state-led prebunking campaigns raise issues of state overreach and potential censorship. Critics warn of unintended suppression of dissenting voices under the guise of narrative protection [12]. To prevent misuse, STRIDE should embed multi-stakeholder oversight, civil liberties audits, and judicial review. These guardrails ensure that interventions remain proportionate and democratically accountable.

Another challenge is inoculation fatigue. Excessive exposure to alerts and counter-narratives may lead to desensitisation or psychological reactance, where individuals perceive such efforts as manipulative and reinforce false beliefs [27]. In polarised contexts, this risk is heightened. To address it, inoculation campaigns should employ rotating localised content delivered through trusted in-group communicators.

The final limitation lies in the ongoing AI arms race. As detection systems improve, adversarial techniques such as style transfer and watermark evasion evolve in parallel. This dynamic requires continuous investment in R&D, collaborative data-sharing, and agile standards development through institutions like Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) and ITU [16].

6.3. Institutional Fit and Real-World Feasibility

STRIDE is aligned with multiple institutional efforts. The EU’s DSA introduces risk audits and trusted flagger mechanisms. NATO’s CCDCOE emphasises hybrid warfare preparedness, while Meta’s Oversight Board illustrates the feasibility of private sector governance in content moderation. UNESCO and WHO (2024) [45] advocate for public resilience through media literacy and misinformation tracking [16].

Operationalising STRIDE, however, demands sustained coordination and legal support. Establishing national-level social cybersecurity councils could institutionalise its functions, ensuring consistency, funding, and cross-sector alignment.

6.4. Future Directions and Research Needs

Several future directions can emerge. Pilot testing in real-world events, such as elections or pandemics, would validate effectiveness. Cross-cultural research is also essential to assess how inoculation and regulatory strategies perform in diverse contexts. The development of standardised metrics, such as resilience indicators, response latency, and coordination efficacy, remains a critical need. Moreover, STRIDE should be expanded to address future threats from autonomous propaganda agents and multi-agent misinformation swarms.

Overall, STRIDE is both theoretically grounded and practically viable. While it does not eliminate disinformation, it strengthens societal capacity to detect, absorb, and respond to coordinated manipulation. The concluding section synthesises these findings and presents actionable recommendations for policy and implementation.

7. Policy Recommendations

To effectively operationalise the proposed STRIDE framework and strengthen digital resilience against AI-driven information manipulation, a set of multi-layered policy actions is necessary. These recommendations are aligned with the framework’s four core layers – detection, regulation, inoculation, and coordination – and are designed to promote scalability, cross-sector engagement, and evidence-informed governance.

7.1. Detection and Attribution

Effective narrative threat mitigation begins with timely and reliable detection. It is recommended that large online platforms, in particular VLOPs and very large online search engines (VLOSEs) under the EU’s DSA, be legally mandated to implement certified AI-based detection systems. These systems must operate in real time for high-risk scenarios, such as elections and public health emergencies, support auditability by national regulators and researchers, and provide explainable outputs with confidence scores to ensure transparency.

In parallel, there is a critical need for the development of open standards for media provenance. International bodies, such as ITU, IEEE, and UNESCO, should lead efforts to standardise cryptographic watermarking of synthetic media, tamper-evident metadata, and audiovisual content chain-of-custody protocols. These technical standards would improve interoperability and facilitate forensic verification of suspected media artifacts.

Public–private intelligence collaboration is also essential. Federated threat intelligence hubs, comprising platforms, regulators, and independent experts, should be established to facilitate cross-jurisdictional data-sharing, flag emerging disinformation narratives, and integrate real-time alerts for high-velocity botnets [15]. Such hubs can function as early warning systems and reduce latency in coordinated response efforts.

7.2. Legislation and Regulatory Oversight

Policy frameworks must be recalibrated to recognise narrative manipulation as a systemic threat. Existing legal instruments, including the EU’s AI Act and DSA, should be revised to explicitly classify narrative-based disinformation as a high-risk category. Legal triggers should be embedded that activate obligations based on virality thresholds and require timely incident reporting once disinformation is detected.

Moreover, regulatory mandates should compel platforms to label all AI-generated content with visible and machine-readable disclaimers. Users must be provided with tools to verify content provenance, and harmful synthetic content linked to public harms should be removed within 24 hours. Enforcement mechanisms should include progressive penalties such as fines, content restrictions, and judicial injunctions to ensure compliance.

To uphold civil liberties, all regulatory interventions must be subjected to judicial oversight and guided by principles of proportionality and necessity. Independent multi-stakeholder governance boards, modelled after structures such as the Meta’s Oversight Board, should audit these interventions regularly to safeguard democratic accountability and procedural fairness.

7.3. Public Inoculation and Digital Literacy

Strengthening societal resilience requires the institutionalisation of inoculation-based education across public systems. National education ministries should incorporate media and AI literacy modules into curricula at multiple levels:

In primary and secondary education, students should be equipped with critical thinking and misinformation-detection skills.

In universities, students should be exposed to advanced topics such as narrative manipulation and AI awareness.

In civic education and public broadcasting, practical scenario-based learning tools such as gamified simulations (e.g. ‘Bad News’) should be employed [27].

In addition to structural education, real-time narrative forewarning systems should be deployed by health ministries, election commissions, and public information authorities. These alerts, distributed via SMS, platform notifications, and trusted intermediaries such as teachers, doctors, and religious leaders, should be timely culturally contextualised and designed to precede, rather than follow disinformation surges.

To operationalise public inoculation, governments must fund and sustain networks of trusted local messengers. These may include healthcare professionals during health crises, election monitors during democratic cycles, and civic leaders within local communities. Positioned as first-line communicators, these actors are instrumental in enhancing credibility and fostering trust in contested information environments.

7.4. Cross-Sector Coordination

A national level architecture is needed to manage disinformation crises in a coordinated and sustained manner. It is recommended that governments establish permanent social cybersecurity councils that bring together cybersecurity, health, education, and media stakeholders. These councils would maintain threat response playbooks, conduct regular red-teaming simulations, and be authorised to make rapid decisions in dynamic threat environments.

At a transnational level, the formation of a multilateral disinformation resilience consortium, potentially anchored under NATO’s CCDCOE or a new United Nation (UN)-led initiative, should be prioritised. This consortium would support intelligence-sharing, harmonise regulatory language, and coordinate joint training and simulation exercises. Engagement with private platforms and research universities would ensure the technological and institutional interoperability of detection and response systems.

Finally, sustained public investment in disinformation crisis readiness is imperative. Governments should fund pilot programs for scenario modelling and behavioural research into counter-narrative effectiveness. Real-time dashboards capable of monitoring public trust levels and tracking the virality of disinformation narratives can serve as critical feedback tools to refine governance strategies and anticipate emerging threats. Table 6 provides a summary of all policy recommendations.

Table 6

Summary of policy recommendations.

7.5. Guiding Principles for Implementation of STRIDE

Besides the above-mentioned policy recommendations, when enacting these recommendations, certain guiding principles should underpin all efforts to ensure they uphold democratic values and are effective:

These policy recommendations translate the study’s theoretical and empirical insights into actionable steps for national and international stakeholders. Implementing them requires coordination, political will, and resources, but the payoff is a strengthened collective defence of democratic society’s information integrity. In the concluding section, we synthesise the contributions of this work and highlight paths forward for research and practice.

8. Conclusions

Artificial intelligence-driven disinformation represents not merely a technological or content challenge but a systemic governance crisis that demands integrated adaptive solutions. This paper has articulated a comprehensive social cybersecurity framework called STRIDE that repositions disinformation as a structural narrative threat, requiring coordinated interventions across detection, regulation, public inoculation, and cross-sector collaboration. STRIDE’s value lies in its capacity to absorb evolving threat signals, adapt legal and civic responses in real time, and foster redundancy through multi-layered engagement. Empirical validation through hypothetical crisis scenarios illustrates the model’s relevance, institutional fit, and policy feasibility across jurisdictions. Moreover, the study identifies key implementation challenges, including jurisdictional fragmentation, potential civil liberty trade-offs, and technological obsolescence while offering concrete mitigation strategies, such as judicial oversight, proportionality principles, and standards-based coordination. The policy matrix and system schematic further provide actionable guidance for operationalising STRIDE. Ultimately, social cybersecurity must move beyond reactive content moderation towards anticipatory governance-oriented resilience. As societies confront increasingly complex generative manipulation threats, the need for digitally literate publics, agile regulatory systems, and cross-sectoral intelligence networks will intensify. STRIDE offers a foundational step towards that future, embedding ethical safeguards, civic capacity, and institutional interoperability into the digital infrastructures of democratic life.