1. Introduction

The escalating number of Internet users and their reliance on online services have led to a significant rise in cyberattacks targeting networks, causing disruptions to their usual operations. As a result, this appears to be contributing to the increasingly complex problem of cyberattacks on systems. Consequently, this issue needs quick attention in order to set up an intrusion detection system (IDS) that constantly monitors the inevitable and never-ending attacks on the Internet. An IDS is a surveillance system developed to observe and identify potentially malicious or unauthorised activities, triggering alerts upon their detection. IDS have consistently served as a safeguarding tool to protect network and information systems [1]. Current IDSs still struggle to provide effective detection services in the face of the ongoing rise in cyber threats to reduce false alarm rates (FAR) and unknown attacks [2]. By employing machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) techniques, researchers investigated the possibilities to enhance the existing conditions and services of IDS. In the last decade, these methods accomplished significant prominence in the field of network security [3].

Misuse detection and anomaly detection are the two categories in to which the IDS are divided according to the detection principles. Misuse detection is alternatively referred to as signature-based detection, and is limited in its ability to identify novel attack techniques, since it can only identify pre-existing patterns. These methods grew more inadequate and unfeasible as network traffic increased exponentially [4]. Conversely, anomaly-based IDS track changes in system behaviour to identify anomalies. Anomaly-based detection, as opposed to abuse detection, is more capable of identifying unknown attacks, thus becoming the focus of the IDS research [2].

However, network intrusion detection systems (NIDS) face many challenges to identify [5] malicious intrusions because of the massive increase in network business and security risks.

Since intrusion detection is considered as a classification problem, researchers have been using deep learning and machine learning methods to enhance the efficacy of IDS. Machine learning approaches have been widely used in IDS, and several researches have demonstrated positive results [6]. The two types of machine learning-based intrusion detection techniques are supervised learning and unsupervised learning. Machine learning techniques, such as in decision trees, logistic regression, AdaBoost, Gradient Boosting, Random forests, K-nearest neighbour classifiers, and Support Vector Machines, commonly employed in supervised learning to identify network behaviour by learning from the labelled data. Unsupervised intrusion detection techniques like hidden Markov models and K-means concentrate on the clustering challenge to classify network behaviours from the unlabelled data. To address the large-scale need, these detection systems also include deep learning techniques, including MLP, long-term short memory (LSTM), recurrent neural networks (RNN), and convolutional neural networks (CNN) are widely utilised for several approaches within the realm of artificial intelligence and machine learning. Further, researchers are interested in determining the best machine learning strategies for enhancing IDS performance [6].

Additionally, the effectiveness of anomaly-based intrusion detection (ID) algorithms in the detection process [7] is significantly affected by challenges such as high dimensionality, noisy data, and data complexity. To address these issues and enhance algorithm performance, a common strategy involves the implementation of data preprocessing, sampling methods and dimensionality reduction techniques. These techniques play a crucial role in mitigating dimensionality concerns, allowing researchers to navigate high-dimensional spaces more effectively [3]. However, there are various feature extraction techniques, like Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), Random Forest Feature extractor, Generalised Discriminant Analysis (GDA), K-best feature selection, and Autoencoders (AE), offering diverse approaches to tackling these challenges.

However, despite the extensive research conducted in the field of IDS, the existing methods still grapple with a substantial false alert rate [8–12] and a minimal detection rate [11, 13–15]. Consequently, there has been a noticeable shift towards leveraging deep learning techniques as a means to alleviate some of these challenges. However, these deep learning approaches still face challenges such as high-dimensional data causing increased training time and resource usage, computational and resource limitations, a high false-positive rate, and the prevalent issue of class imbalance leading to biased classifiers and difficulty in identifying the most informative features critical for distinguishing between normal and attack traffic [9, 11, 16–18]. Our main objective is to provide an effective, lightweight architecture that uses feature engineering to overcome these enduring difficulties, outperforming the state-of-the-art algorithms.

To address these limitations, in this paper, we use a variation of autoencoders for feature extraction. Autoencoders, a class of unsupervised deep learning models, have shown significant promise in network intrusion detection due to their ability to efficiently recognise and encode intricate patterns in data [19]. They consist of three main components: an encoder, a code (latent) layer, and a decoder. The encoder compresses the input into a lower-dimensional representation, which is then used by the decoder to reconstruct the original input. By minimising the reconstruction loss, autoencoders learn hidden and meaningful features from raw input data. Compared to traditional techniques like PCA and LDA, autoencoders offer greater flexibility and improved accuracy in feature extraction for IDS.

In this study, we propose a novel lightweight intrusion detection framework, termed SAE-AM, that combines sparse autoencoders (SAE) with attention mechanisms (channel and positional attention mechanisms) to address both computational complexity and the challenge of high-dimensional feature spaces. SAE enforce sparsity in latent representations, preserving only the most significant activations. The attention modules guide the model to focus on relevant features across the input dimensions, boosting the model’s ability to capture global dependencies. To further enhance the detection of rare attacks, we adopt a hybrid resampling strategy using Random Under-Sampling (RUS) and SMOTE.

Our work makes the following significant contributions:

A novel SAE-AM intrusion detection model is proposed, which integrates attention mechanisms within SAE to effectively detect anomalies in high-dimensional network traffic data.

To address the issue of data imbalance, a hybrid resampling strategy combining RUS and SMOTE has been employed to enhance detection performance across minority classes.

An efficient dimensionality reduction approach using SAE is applied to retain critical information while significantly reducing the input feature space.

The integration of attention modules improves the model’s capability to focus on salient features, resulting in superior classification performance.

The proposed approach has been validated through comprehensive ablation studies and comparisons with state-of-the-art models using various evaluation metrics.

The paper is segmented into the subsequent sections. Section 2 describes overview of the prior research-related work while Section 3 presents the proposed methodology. The dataset descriptions as well as the implementation details are described in Section 4. In Section 5, the evaluation metrics and results of our proposed methodology and the comparison of performance with other models are presented. Section 6 provides the findings at the end.

2. Related Works

Over the years, various approaches leveraging machine learning, deep learning, and hybrid learning techniques have been proposed to enhance the efficiency and accuracy of IDS. This section reviews significant contributions in these areas, highlighting innovative methodologies and their experimental validations on benchmark datasets. By systematically evaluating and contrasting various methodologies, results, and conclusions, this review provides a clear understanding of the current state of research as described in Table 1. It highlights key trends and advancements, thereby identifying areas for future investigation.

Table 1

Literature review on related studies.

| Ref. | Year | Methodology | Datasets | Results | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [34] | 2021 | ADASYN+ Light GBM | CICIDS2017 NSL-KDD UNSW-NB15 | 99.91 92.57 85.89 | Oversampling complexity can lead to highercomputational costs |

| [23] | 2022 | CNN-RSA | CICIDS2017 NSL-KDD KDDCUP99 BoT-IoT | 99.99 99.23 99.9 99.99 | Complexity and computational cost |

| [35] | 2022 | BMRF+RF | CICIDS2017 NSL-KDD | 99.3 98.8 | Slow execution time More dependency on classifier |

| [10] | 2023 | GWO+RF | CICIDS2017 NSL-KDD KDDCUP99 | 96.25 94.64 94.43 | Complexity and overhead uncertain feature selection impact |

| [32] | 2023 | IG-FCBF+CNNmodels | CICIDS2017 NSL-KDD | 99.85 99.53 | More dependency on CNN models |

| [22] | 2023 | BIRCH-AE | CICIDS2017 NSL-KDD KDDCUP99 UNSW-NB15 | 92.58 87.88 87.61 95.95 | Low performance results |

| [36] | 2023 | Multi-head Attention+BiLSTM | CICIDS2017 NSL-KDD KDDCUP99 | 99.08 95.19 98.28 | Imbalanced training data Complex model leads to high computationalcost |

| [37] | 2023 | CBF+CNN-BiLSTM | CICIDS2017 NSL-KDD UNSW-NB15 | 99.53 99.40 82.30 | Increased model complexity High computational demands |

| [38] | 2023 | SMOTE+CatBoost | CICIDS2017 NSL-KDD UNSW-NB15 | 99.66 99.26 98.70 | Complex implementation |

| [9] | 2023 | CNN+LSTM | CICIDS2017 NSL-KDD UNSW-NB15 | 99.15 98.17 98.81 | Hybrid model leads to complex implementation |

| [39] | 2023 | EIDM | CICIDS2017 | 95 | Deployment of multiple DL models require significant computational resources |

| [30] | 2023 | CNN+LSTM | UNSW-NB15 X-IIoTID | 93.21 99.84 | Deployment of multiple DL models require significant computational resources |

| [31] | 2024 | OOA+Bi-LSTM | CICIDS2017 ToN-IoT N-BaIoT | 99.97 99.88 99.98 | More computationally resource-intensive |

| [21] | 2024 | ML models | CICIDS2017 NSL-KDD UNSW-NB15 | 99.90 97.50 98.60 | Low performance on UNSW-NB15 dataset |

| [12] | 2024 | GSWO-CatBoost | CICIDS2017 NSL-KDD WSN-DS WSNBFSF | 99.74 99.76 99.62 99.99 | More complex model |

2.1. Machine Learning-Based Approaches for IDS

Liu et al. [12] proposed a NIDS that leverages adaptive synthetic (ADASYN) oversampling technology and the Light GBM ensemble learning model. To tackle the problem of data imbalance, ADASYN oversampling is employed, and Light GBM is used as the classifier. Experimental validation on the NSL-KDD, UNSW-NB15, and CICIDS2017 datasets demonstrates the system’s high detection accuracy of 89.79%, 83.98%, and 99.86%, respectively.

Hassan et al. [20] present a network intrusion detection model using an improved Binary Manta Ray Foraging (BMRF) Optimisation Algorithm and a Random Forest (RF) classifier. The BMRF algorithm, enhanced with adaptive S-shaped transfer functions, is used to choose the most pertinent features from intrusion detection datasets (NSL-KDD and CICIDS2017). However, it lags behind Naïve Bayes and XGBoost in execution time. Future work includes exploring other classifiers to improve the BMRF algorithm for better feature selection and more efficient handling of data imbalance.

Das et al.’s [21] study introduces an ensemble-based machine learn-ing approach to detect Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks. It combines supervised and unsupervised ensemble frameworks to achieve higher performance in detecting both known and unknown DDoS attacks. The supervised ensemble focuses on known attacks, while the unsupervised ensemble is effective in identifying previously unseen attacks through novelty and outlier detection. Experimental results using three benchmark datasets demonstrate the robustness and effectiveness of the proposed scheme in accurately detecting DDoS attacks with minimal false alarms.

Nguyen et al. [22] introduces a novel approach called Genetic Sacrificial Whale Optimisation (GSWO) to improve intrusion detection in Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs). GSWO integrates a genetic algorithm (GA) and a modified whale optimisation algorithm (WOA) to overcome premature convergence and enhance global search capabilities. Furthermore, the CatBoost model is used for classification, adeptly managing categorical data with intricate patterns. A novel method for fine-tuning CatBoost’s hyperparameters is introduced, utilising quantisation and the GSWO strategy, resulting in improved intrusion detection accuracy and real-time applicability.

2.2. Deep Learning-Based Approaches for IDS

Dahou et al. [23] designed a framework that integrates deep learning and metaheuristic optimisation algorithms for feature extraction and selection in Internet of Things (IoT) and cloud IDS. A CNN is used for feature extraction, while a novel feature selection method called Reptile Search Algorithm (RSA) optimises feature subset selection. Experimental results demonstrate RSA’s superior performance over other optimisation methods as well as in testing scenarios. Future work includes improving RSA’s convergence speed and exploring its application in training deep learning models for various IDS applications.

Yan et al. [24] introduces TL-CNN-IDS, an IDS based on transfer learning and ensemble learning. It employs feature engineering methods for enhanced model training, visualises network traffic data as images for CNN training, and utilises three CNN models (VGG16, Inception, and Xception) with hyperparameter optimisation and ensemble learning for improved intrusion detection. Evaluation on CICIDS2017 and NSL-KDD datasets demonstrates efficient detection of various network attacks. Future work may focus on addressing dataset imbalances and classifying emerging threats using small-sample learning algorithms.

J. Zhang et al.’s study [25] proposes a network intrusion detection model that integrates a multi-head attention mechanism and Bi-directional LSTM (BiLSTM). The model uses embedding layers to convert high-dimensional feature vectors into low-dimensional ones, enhancing the information fusion. Multi-head attention assigns different weights to each vector, improving the detection accuracy by strengthening the relationships between vectors and attack types. BiLSTM captures long-distance dependencies in the data, further improving detection accuracy. A dropout layer is added to prevent overfitting. Experimental results demonstrate that the model surpasses others in accuracy and F1-score on the KDDCUP99, NSLKDD, and CICIDS2017 datasets.

Ullah et al. [26] proposed IDS for Imbalanced Network Traffic (IDS-INT), leverages transformer-based transfer learning to learn feature interactions in network traffic and uses the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) to balance the dataset. Experiments conducted on UNSW-NB15, CIC-IDS2017, and NSL-KDD datasets demonstrate the effectiveness of IDS-INT on multi-class classification. Additionally, an explainable artificial intelligence approach is implemented to interpret the model, enhancing its trustworthiness and reliability.

Elnakib et al. [27] introduces an Enhanced Intrusion Detection Deep Learning Multi-class classification model (EIDM), designed to classify various types of attacks. The EIDM model is noted for its ability to classify all 15 classes individually without grouping similar classes, marking a significant advancement in IDS technology for IoT.

2.3. Hybrid Learning-Based Approaches for IDS

C. Zhang et al. [28] introduce a novel approach to abnormal traffic detection by addressing the uncertainty of samples in the dataset. This model integrates the concept of three-way decision into the random selection of feature attributes and evaluates attribute importance using decision boundary entropy. Additionally, a classifier evaluation function combining accuracy and diversity selects high evaluation value-based classifiers, and the gray wolf optimisation algorithm iteratively calculates optimal node weights to enhance prediction accuracy and robustness.

Wang et al. [29] introduces an outlier-detection algorithm for network traffic anomalies that integrates the BIRCH clustering algorithm with an autoencoder model. BIRCH pre-classifies datasets with complex data distributions, and the autoencoder detects outliers by setting a threshold. Validated on datasets, such as KDDCUP99, UNSW-NB15, CICIDS2017, and NSL-KDD, the BAE algorithm has demonstrated effective and accurate anomaly detection. However, the algorithm’s computational complexity is high, and exploring alternative pre-classification algorithms and advanced autoencoders is necessary for better performance.

Altunay and Albayrak’s [30] study proposed three deep learning models – CNN, LSTM, and a hybrid CNN+LSTM model – to detect intrusions in Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) networks. Using the UNSW-NB15 and X-IIoTID datasets, both binary and multi-class classifications were conducted to identify normal and abnormal data. The models also demonstrated success in accurately detecting various attack types within the datasets. Addressing potential memorisation issues by incorporating synthetic data generation into the datasets and retraining the models is efficient.

Chintapalli et al. [31] proposed an efficient IDS, combining the Osprey Optimisation Algorithm (OOA) for feature selection and a modified Bi-LSTM network using the Exponential Linear Unit (ELU) activation function. The framework was tested on N-BaIoT, CICIDS2017, and ToN-IoT datasets, achieving high detection accuracies of 99.98%, 99.97%, and99.88%, respectively, along with reduced processing times. This IDS framework demonstrates a robust solution for protecting IoT systems from various cyber threats.

Peng et al. [32] introduces CBF-IDS, a new network intrusion detection system that combines CNNs and BiLSTMs with the focal loss function to address class imbalance. CBF-IDS efficiently extracts spatial and temporal features from network traffic and assigns higher weights to minority classes during training to improve performance. Despite its effectiveness, the hybrid model has increased complexity and computational demands.

Zhang and Wang [33] introduce a novel intrusion detection classification approach that integrates advanced feature engineering techniques and model optimisation. It utilises mutual information maximum relevance minimum redundancy (mRMR) feature selection and the synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE) to enhance classifier accuracy by reducing feature redundancy and addressing class imbalance. Additionally, the Optuna method is employed to optimise the hyperparameters of the CatBoost classifier, thereby enhancing the model’s performance. It is evaluated on NSL-KDD, UNSW-NB15, and CICIDS2017 datasets.

The reviewed studies demonstrate significant advancements in the field of network intrusion detection, utilising a diverse array of machine learning, deep learning, and hybrid learning techniques. Overall, the continual evolution of IDS technologies through machine learning, deep learning, and hybrid learning approaches provides robust and effective solutions for countering the ever-growing threat of cyberattacks. Future research in this domain is expected to focus on refining these techniques, addressing computational complexities, and exploring new algorithms to maintain the efficacy and reliability of IDS in dynamic network environments.

2.4. Critical Analysis of Related Works

The literature reveals a growing trend in the application of machine learning, deep learning, and hybrid learning approaches for developing efficient IDS. These methods have demonstrated substantial promise in enhancing detection capabilities, especially in complex and evolving network environments. A notable strength observed in several studies is the effective handling of class imbalance through techniques such as ADASYN [12], SMOTE [33], and focal loss, which contribute to improved model generalisation. Additionally, the incorporation of metaheuristic optimisation algorithms – including GSWO [22], RSA [23], Opposition-based Owl Optimisation [31], and Binary Multiverse Relevance Feature Selection (BMRF) [20] – has led to significant advancements in feature selection and, consequently, better detection accuracy.

Hybrid models such as CNN+BiLSTM [32], CNN+LSTM [30], and CatBoost integrated with GWO [22], successfully combine spatial and temporal learning capabilities, offering robust intrusion detection performance in dynamic IoT and IIoT environments. Furthermore, ensemble learning and transfer learning techniques, including models like TL-CNN-IDS, have been adopted to enhance adaptability to emerging threats and improve detection rates across varying attack scenarios.

Despite these strengths, several limitations persist. The computational complexity and extended processing time associated with many hybrid and optimisation-based models pose a significant challenge, particularly in real-time or resource-constrained applications. Moreover, certain studies demonstrate a heavy reliance on specific classifiers such as LightGBM [12] and CatBoost [22], which may restrict the generalisability of the proposed frameworks. A lack of standardisation in evaluation protocols and performance metrics across different datasets further complicates direct comparisons and objective assessments. Additionally, overdependence on synthetic sampling techniques like SMOTE and ADASYN can introduce the risk of overfitting or create unrealistic training conditions.

Several key research gaps have also been identified. The most current studies are confined to benchmark datasets such as NSL-KDD, CICIDS2017, and UNSW-NB15, with limited validation on real-world, encrypted, or highly imbalanced datasets. Furthermore, only a few works have considered adversarial threats such as data poisoning or evasion attacks, despite their increasing relevance in cybersecurity.

3. Methodology

In this section, we delineate the proposed methodology illustrated in Figure 1 and as shown in algorithm in Figure 2. SAE were employed for dimensionality reduction, aiming to decrease the number of features. In addition to that, attention modules are incorporated for the encoder part of SAE. A classifier, multi-layer perceptron (MLP) is used for classifying the binary and multi-class classification.

3.1. Sparse Autoencoders

Sparse autoencoders are a specialised type of autoencoders, which introduce L1 regularisation at the code layer, encouraging sparsity in hidden layer activations as depicted in Figure 3. This regularisation, applied through a penalty term in the loss function, promotes selective activation of neurons during training. The mean computed across training samples needs to be close to zero to meet the sparsity requirement [37, 39]. Unlike standard autoencoders, where all neurons can be activated simultaneously, SAE impose constraints to encourage more selective activation.

Training a sparse autoencoder involves optimisation of weights and biases to simultaneously minimise reconstruction error and satisfy sparsity constraints. This process facilitates dimension reduction, ultimately enhancing prediction accuracy with less training time [40]. SAE, characterised by their sparsity constraints on weights, are particularly valuable when a sparse and meaningful representation is desired and excels at compressed feature extraction, making them particularly suitable for applications like network intrusion detection. This suitability becomes especially beneficial in scenarios where interpretability or efficiency is of paramount importance.

Sparse autoencoders are particularly well-suited for network intrusion detection because they go beyond mere dimensionality reduction by learning compact and highly informative representations of input data. The sparsity constraint forces the model to activate only a limited number of neurons for any given input, leading to the extraction of critical, non-redundant patterns in network traffic [41, 42] This selective activation helps in identifying subtle and rare anomalies often present in malicious activities. In intrusion detection, where attack behaviours can be infrequent and masked by normal traffic, such focused representations improve the ability to detect anomalies and enhance classifier performance [43]. Moreover, SAE demonstrate robustness to noise and help mitigate the effects of data imbalance, making them a powerful feature extraction technique in the cybersecurity domain [44, 45]

3.2. Self-Attention Modules

The attention mechanism, inspired by human focus on key regions or words, is crucial for addressing intra-class differences and extracting context-rich information [46]. Following the encoder–decoder framework, attention selectively emphasises specific data segments by mapping queries to key-value pairs [36, 47].

Our approach incorporates attention modules to improve predictions by highlighting relevant feature sequences, assisting in detecting suspicious activities. Visualising attention probabilities reveals feature importance across traffic classes, enhancing model interpretability and adaptability through both positional and channel-wise attention.

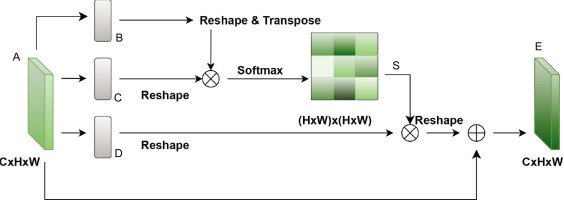

3.2.1. Positional Self-Attention Module

Positional attention, on the other hand, is based on the transformer architecture and captures dependencies between features that may follow a temporal or sequential pattern. Features like connection duration, protocol sequences, or timing information often contain contextual clues that are crucial for identifying complex or stealthy attacks. Positional attention enables the model to capture such long-range interactions by modeling the relationships between features regardless of their positions [36]. This is further supported by the idea of non-local operations, where the output at any position depends on the weighted sum of all positions in the input, giving the model a global perspective [34].

The positional self-attention module as shown in Figure 4 captures positional relationships within sequences, enhancing the model’s contextual understanding [48]. Starting from a local feature A ∈ RC×H×W, convolutional layers with batch normalisation and standard rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation produce feature maps B and C, reshaped to RC×N. A spatial attention map S ∈ RN×N is then calculated as:

Meanwhile, A is processed to generate a new feature map D, reshaped to RC×N. A matrix multiplication between D and ST is reshaped to RC×H×W, scaled by a parameter α, and added to A to yield the final output E:

Starting from zero, α gradually increases, adjusting feature weights. This operation combines information from all positions, enriching the model’s global contextual awareness.

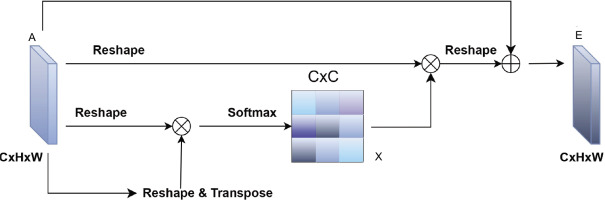

3.2.2. Channel Self-Attention Module

Channel attention helps the model identify and emphasise the most relevant feature channels by learning to assign different importance weights to each input feature. In the context of intrusion detection, where certain features like packet rates or byte counts are more informative, channel attention allows the model to focus on these critical features and reduce the influence of less relevant or noisy inputs. This concept is inspired by the squeeze-and-excitation networks, which have shown improved performance in various deep learning models by adaptively recalibrating feature responses [34].

The channel self-attention module, depicted in Figure 5, enhances model focus on key features by emphasising relevant channels and suppressing less useful ones [47, 48]. Unlike positional attention, which captures spatial dependencies, the channel attention map X ∈ RC×C is computed by reshaping features A ∈ RC×H×W, performing matrix multiplication with its transpose, and applying softmax:

The final output E is achieved by scaling and summing weighted channels with the original features:

This approach highlights class-specific channels, enhancing feature representation and model discriminability.

By combining both attention mechanisms, the model benefits from a dual focus: it learns which features are important (via channel attention) and how these features interact or evolve (via positional attention). This significantly enhances the model’s ability to capture subtle patterns in high-dimensional network data, ultimately improving its effectiveness in detecting intrusions.

3.3. Multi-Layer Perceptron

A multilayer perceptron is a type of neural network known for its ability to model complex nonlinear relationships, making it well suited for high-dimensional data processing. Although MLPs were once considered state-of-the-art, they remain effective due to their adaptive learning capabilities, allowing them to adjust dynamically based on training data [49]. MLPs are among the most commonly used types of Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) due to their straightforward architecture, minimal training requirements, and versatility. This layered architecture enables MLPs to learn intricate relationships, which is particularly useful in intrusion detection scenarios where data is often high-dimensional and nonlinear.

One of the key reasons MLPs are frequently employed in IDS is their capacity to automatically learn complex patterns without the need for extensive manual feature engineering [50]. MLPs function as feedforward networks, where data is passed from the input through hidden layers to the output. Learning is facilitated through back propagation, which iteratively adjusts the model’s weights and biases to minimise prediction errors and improve performance [51].

Although other classifiers like Support Vector Machines (SVMs) are widely used, MLPs offer distinct advantages. While SVMs perform well for binary classification tasks, they often struggle with scalability in large, high-dimensional datasets [52, 53] In contrast, MLPs are more effective at handling such data by capturing complex, nonlinear decision boundaries [35]. Additionally, MLPs integrate seamlessly with deep learning frameworks, providing better scalability and adaptability for tasks like intrusion detection [54]. In this study, the MLP is chosen for its ability to model complex, nonlinear relationships in high-dimensional IDS datasets [55, 56]. MLPs are particularly well suited to process the latent representations generated by SAE, enabling a seamless and efficient deep learning pipeline [55, 57]. Furthermore, MLPs support gradient-based optimisation, making them easier to train and more compatible with modern deep neural network architectures compared to traditional classifiers such as SVMs [36, 56].

Moreover, MLPs are versatile and can be effectively combined with advanced techniques such as SAE and attention mechanisms. This integration enhances both feature extraction and classification accuracy by enabling the model to focus on the most relevant features in the data [50, 58]. Therefore, among the various machine learning methods, the multilayer perceptron stands out, making it a focal point in this study’s classification stage.

4. Datasets

4.1. CICIDS2017 Dataset

The CICIDS2017 dataset, created by the Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity, is a comprehensive collection of labeled network traffic data designed for studying various cyberattacks within a simulated network environment. This dataset is widely used in the intrusion detection research community due to its diverse range of attack types and realistic representation of network traffic. Collected over five consecutive days (Monday to Friday) in July 2017, the dataset includes both benign and malicious activities, making it well suited for training and evaluating IDS and other cybersecurity tools.

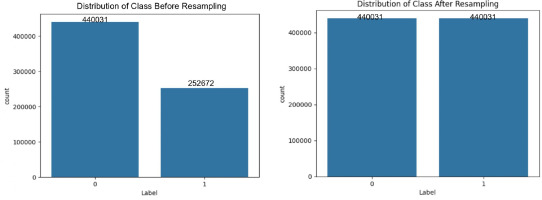

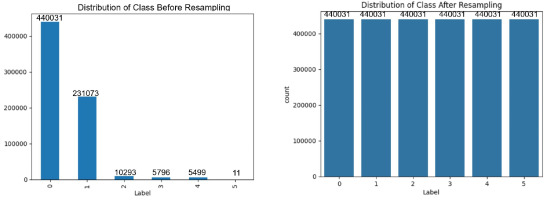

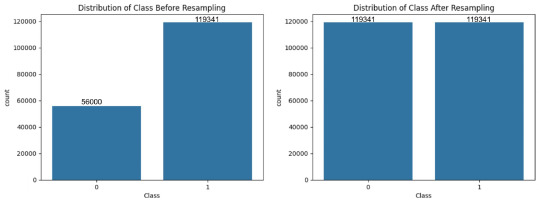

The dataset comprises 692,703 samples with 80 attributes, covering various aspects of network behaviour – ranging from basic packet-level details to advanced time- and host-based features. To further clarify our preprocessing steps, Figures 6 and 7 depict the distribution of attack categories before and after applying resampling techniques for both binary and multi-class classification tasks.

4.2. NSL-KDD Dataset

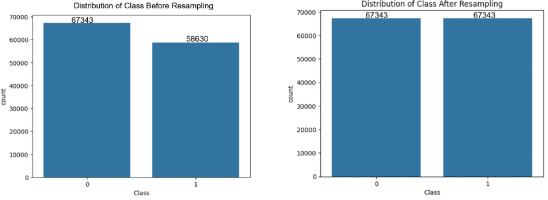

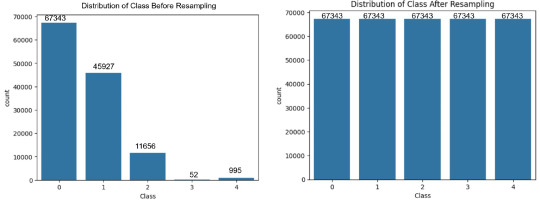

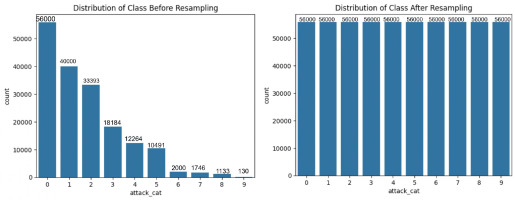

The NSL-KDD dataset, commonly employed for network intrusion detection, serves as an effective benchmark for comparing various intrusion detection methods and is acknowledged for its popularity. However, a notable drawback is the presence of numerous redundant records, potentially impacting the efficacy of evaluated systems. To overcome this issue, researchers built a new refined dataset named NSL-KDD dataset. There are 125,973 records in the KDDTrain+ and 22,544 records in the KDDTest+ dataset with 42 features each. Among the 42 features, we found 6 binary, 3 category, 32 numerical are input attributes, and 1 class label. The datasets contain 22 and 38 attack types in the KDDTrain+ and KDDTest+ datasets, respectively. These attack types are categorised into four primary kinds: DoS, Probe, U2R, and R2L. Figures 8 and 9 illustrate the class-wise distribution of attacks prior to and following the application of resampling techniques, for both binary and multi-class classification scenarios.

4.3. UNSW-NB15 Dataset

The UNSW-NB15 dataset, derived from real network traffic data generated by IXIA PerfectStorm, encompasses a wide variety of attack types alongside normal traffic. This dataset is highly regarded for its realism, offering scenarios that closely mimic actual network conditions, unlike some synthetic datasets. The dataset includes separate training and testing sets, with 175,341 and 82,332 records, respectively, each containing 43 original features. After converting categorical features into binary representations, the dataset expands to 194 features, enhancing its complexity and usability for machine learning-based IDS development. Figures 10 and 11 present the comparison of attack class distributions before and after resampling, highlighting the impact of the applied techniques on both binary and multi-class classification tasks.

For all the three datasets, we used a standard 80-20 split for training and testing the models, where 80% of the samples were allocated for training and 20% for testing. These datasets are frequently used in network intrusion detection for evaluating and comparing different intrusion detection methods. They are a comprehensive collection of labeled network traffic data designed for studying various cyberattacks within a simulated network environment. These datasets are highly regarded for their realism, offering scenarios that closely mimic actual network conditions, unlike some synthetic datasets. The datasets include both benign and malicious activities, making it suitable for training and evaluating IDS and other cyber-security tools.

5. Implementation

Our proposed methodology has been implemented on Windows 11 operating system environments with AMD Ryzen 7 7730U with Radeon Graphics processor, 16GB RAM, and Python 3.10.12 version using Keras library with TensorFlow as back end. For the proposed methodology, the experiments, training, and testing were conducted using the popular benchmark CICIDS2017, NSL-KDD, and UNSW-NB15 datasets.

5.1. Data Preprocessing

In the data preprocessing stage, out of the 42 and 43 features in the NSL-KDD and UNSW-NB15 datasets, respectively, we identified 37 numeric features and three non-numeric features. One-hot encoding is used in the dataset to encode non-numeric characteristics. For instance, the three-attribute protocol type in the datasets is substituted with three-dimensional (3D) vectors (1, 0, 0), (0, 1, 0), and (0, 0, 1). Finally, the NSL-KDD dataset contains 121-dimensional and the UNSW-NB15 dataset contains 194 characteristics after conversion. Additionally, we use Min-Max normalisation to normalise the data. Using this method, all the scaled data is obtained in the interval (0, 1).

5.2. Resampling Method

The NSL-KDD and UNSW-NB15 datasets exhibit notable class imbalance, where certain attack categories have significantly fewer instances, compared to others. This imbalance can lead to biased model learning, where the classifier favors majority classes and performs poorly on minority classes. Additionally, the presence of high-dimensional data with redundant and noisy features can further degrade model performance.

To address these challenges, we employed a two-fold strategy: (1) balancing the class distribution using resampling techniques, and (2) reducing dimensionality through feature extraction. For resampling, we utilised both Random Under Sampling (RUS) and Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE). RUS reduces the sample size of the majority class, while SMOTE generates synthetic samples for the minority class to balance the dataset.

The datasets were split into training, validation, and testing sets, and resampling was applied only to the training set to avoid data leakage. The specific number of samples before and after resampling for both binary and multi-class classification tasks are shown in Figures 6–11. This balanced and compact representation enhances the model’s ability to generalise, reduces computational complexity, and improves detection accuracy across both frequent and rare attack types.

5.3. Feature Extraction Through Sparse Autoencoders with Attention Modules

For the effective feature extraction method, we integrated SAE with attention modules. SAE consist of three primary layers: the encoder layer, the code layer, and the decode layer.

To enforce sparsity in the learned representations, L1 regularisation is applied, encouraging many weights in the code layer to be exactly zero. The model further integrates channel and positional attention modules, enhancing its ability to capture long-range dependencies and relationships within the input data. This architecture combines the feature-learning capabilities of SAE with channel attention in convolutional layers to adaptively weight channels and positional attention in transformer layers to capture sequence information. The decoder reconstructs the encoded data, utilising a sigmoid activation function in the output layer, while all other layers employ the ReLU activation function. The SAE-AM model is trained for up to 20 epochs, minimising reconstruction loss, with the mean square error (MSE) used to quantify the difference between actual and predicted values across the dataset.

In this experiment, we utilised the CICIDS2017, NSL-KDD, and UNSW-NB15 benchmark pre-processed datasets, which contain 79, 121, and 194 features, respectively. The dimensionality of these datasets was reduced to 30 features using the sparse autoencoder before being fed into a classifier. Our methodology combines the sparse autoencoder with L1 regularisation and attention modules to refine and optimise feature sequence predictions. The encoded features undergo both channel and positional attention mechanisms, demonstrating a synergistic relationship between SAE and attention modules.

5.4. Classifier

As shown in Table 2, the classifier, MLP comprises three dense layers with 160, 80, and 40 units, respectively, and an output layer with 2 units. Dropout layers (with a rate of 0.5) are inserted between hidden layers for data regularisation and to mitigate overfitting. The activation function for hidden layers is the ReLU [59], while the final layer uses the sigmoid activation function for binary classification. For multi-class classification, the output layer has six, five, or 10 units, utilising the softmax activation function to generate probability distributions across different classes. The binary cross-entropy loss function quantifies differences between predicted and real labels for binary tasks, while categorical cross-entropy is used for multi-class scenarios. The Adam optimiser, with a learning rate of 0.001, is employed for optimising model parameters.

Table 2

Summary of the MLP model.

5.5. Hyperparameter Tuning

To select the best model parameters for feature extraction, we performed hyperparameter tuning as shown in Table 3, using a reduced feature set of 30 and a lambda (λ) for regularisation strength. The optimal configuration of SAE integrated with attention modules was selected based on minimising validation loss, ensuring fine-tuned model performance.

Table 3

Hyperparameter tuning results.

In designing the SAE, we adopted a three-layer architecture comprising an encoder, a code layer, and a decoder. This struc-ture was chosen to balance complexity and performance, providing sufficient capacity for compressing high-dimensional input features into a reduced and informative representation. Specifically, the input features from datasets such as CICIDS2017 (79 features), NSL-KDD (121 features), and UNSW-NB15 (194 features) were compressed into 30 latent features. This dimensionality reduction was selected based on empirical trials to preserve essential information while reducing noise and computational cost. To determine the optimal number of features for downstream classification, we conducted experiments with varying dimensionalities of the latent representation, specifically exploring feature sizes of 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50. We selected 30 as the optimal feature size based on empirical evaluation, where it consistently provided the best balance between classification accuracy and model complexity across all datasets. Reducing the features to 30 allowed the model to retain the most informative characteristics of the data while minimising redundancy and computational overhead. This configuration was particularly effective in improving generalisation performance without sacrificing important patterns necessary for accurate intrusion detection.

To determine the optimal sparsity level in the latent representation, we performed hyperparameter tuning by varying the L1 regularisation parameter (λ) within the range {0.0001, 0.001, 0.01, 0.1}. This parameter enforces sparsity in the code layer of the SAE, encouraging the network to learn compact and discriminative feature representations. Based on extensive validation experiments, λ = 0.001 was identified as the optimal value, striking a balance between sparsity and reconstruction accuracy. We employed the ReLU activation function in the encoder and decoder layers due to its efficiency and ability to model nonlinear patterns, while the final decoder layer used a sigmoid activation to reconstruct normalised inputs within the (0, 1) range.

Furthermore, we integrated channel and positional attention modules into the SAE to enhance its capability to capture long-range dependencies and feature relevance. Channel attention enables the network to focus on the most informative feature channels, while positional attention – drawn from transformer principles – helps model sequential or positional dependencies in the feature set. These modules were included to improve the contextual understanding of feature relationships. This is critical in intrusion detection scenarios, where subtle feature interactions can signal malicious activity.

Regarding the classifier, the MLP was constructed with three hidden layers containing 160, 80, and 40 neurons, respectively, followed by a task-specific output layer. This pyramidal structure enables progressive abstraction and feature transformation, allowing the model to capture complex patterns while mitigating overfitting risks. The sizes of the layers were chosen based on iterative experimentation, where this configuration provided the best performance across validation datasets. Dropout layers with a dropout rate of 0.5 were added after each hidden layer to prevent overfitting and improve generalisation. The Adam optimiser was employed for training both SAE and MLP models due to its robustness and adaptability to different learning conditions. A learning rate of 0.0001 was used for training the SAE to ensure stable convergence during feature extraction, while a learning rate of 0.001 was optimal for training the MLP. These values were selected from a range of candidates during the hyperparameter tuning process, as detailed in Table 3. The choice of activation functions in the MLP followed common best practices: ReLU for hidden layers due to its non-saturating nature and computational efficiency, and sigmoid or softmax in the output layer depending on whether the classification task was binary or multi-class, respectively.

Overall, the architecture and hyperparameters were selected through rigorous experimentation and tuning to achieve an optimal balance of model accuracy, complexity, and interpretability, particularly in the context of high-dimensional, real-world intrusion detection datasets.

6. Results and Discussion

The model’s performance is evaluated using a confusion matrix and several key metrics, which provide insights into the model’s effectiveness. These metrics – accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, FAR, and time (seconds/epoch) – facilitate comparisons with other binary and multi-class classification models.

Our proposed technique, SAE-AM, demonstrated superior performance compared to state-of-the-art algorithms on benchmark datasets, such as CI-CIDS2017, NSL-KDD, and UNSW-NB15, as shown in Table 4. These results underscore SAE-AM’s reliability and effectiveness as a solution for NIDS, particularly in addressing the complex challenges posed by evolving cyber threats.

Table 4

Performance results (in %) of proposed SAE-AM methodology.

To further validate the robustness of the SAE-AM model and address concerns about potential overfitting due to high accuracy in binary classification, we present learning curves for both training and validation loss and accuracy in Figure 12. These curves demonstrate that the model exhibits consistent learning behaviour, with training and validation losses steadily decreasing and no signs of divergence across epochs. Similarly, the accuracy curves remain stable, indicating that the model generalises well and does not suffer from overfitting. This further reinforces the credibility of the reported result of 100% of the CICIDS2017 data set using binary classification.

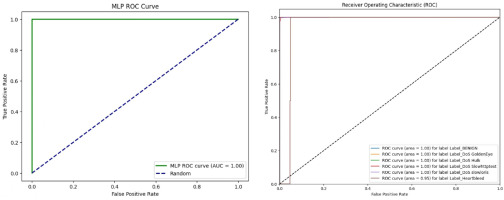

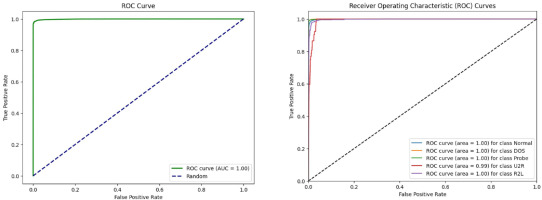

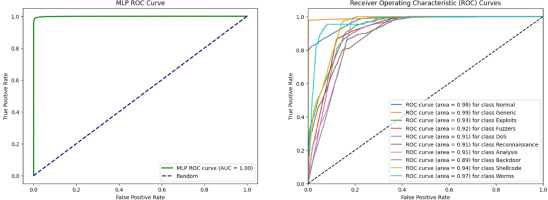

In addition to traditional evaluation metrics, the performance of SAE-AM can be further assessed through Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. ROC curves provide a comprehensive visualisation of the trade-off between the true positive rate (sensitivity) and the false positive rate (1-specificity) across different classification thresholds. A higher Area Under the Curve (AUC)–ROC value indicates superior performance in distinguishing between normal and abnormal classes, particularly in binary classification scenarios.

Figure 13 illustrates the ROC curves for binary and multi-class classifications of the CICIDS2017 dataset, showcasing the model’s discrimination capability across multiple attack types. Additionally, Figure 14 depicts the ROC curves for binary and multi-class classifications of the NSL-KDD dataset. These figures provide visual insights into how well the SAE-AM model performs in terms of sensitivity and specificity thresholds for both datasets. Furthermore, Figure 15 illustrates the ROC curves of binary and multi-class classification of the UNSW-NB15 dataset.

6.1. Ablation Studies

To evaluate the effectiveness of our proposed SAE-AM methodology, we conducted ablation studies across three datasets: CICIDS2017, NSL-KDD, and UNSW-NB15. The core structure of theSAE-AM framework integrates SAE with attention modules for enhanced feature extraction, followed by a MLP classifier to detect and classify various types of attacks. Table 5 presents the results of the ablation experiments, including configurations such as SAE+MLP (without attention modules), AM+MLP (without SAE), and SAE-AM+MLP (our proposed methodology), demonstrating the superiority of the proposed methodology.

Table 5

Ablation study results (in %) across three datasets.

In our ablation studies, we systematically removed specific components of the SAE-AM framework to assess their impact on model performance. We evaluated the importance of SAE, which facilitate dimensionality reduction, and the dual attention modules that capture global dependencies in the data. Additionally, we tested the performance of the MLP classifier without these enhancements.

The results indicate that removing SAE leads to a significant drop in classification accuracy, confirming their essential role in efficient feature extraction and dimensionality reduction. Similarly, excluding the channel and positional attention modules resulted in a marked decline in the model’s ability to capture global relationships, leading to higher FAR. These findings underscore the necessity of both SAE and attention modules in the SAE-AM framework, as they optimise computational efficiency while maintaining high accuracy in detecting both normal and attack samples.

6.2. Comparison Analysis

To comprehensively evaluate the efficacy of our proposed SAE-AM methodology in NIDS, we conducted a comparative analysis using the CICIDS2017, NSL-KDD, and UNSW-NB15 datasets for binary classification and multi-class classification, as shown in Tables 6 and 7, respectively. We benchmarked against various machine learning, deep learning, and hybrid approaches. The performance of various IDS models was assessed based on several key criteria, including the overall accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, FAR, time lapse (seconds/epoch), handling of imbalanced data, feature selection and extraction, model complexity and computational efficiency, robustness and generalisation, and novelty detection.

Table 6

Comparison of proposed method (SAE-AM) with other methods of binary class classification.

| Ref. | Method+classifier | Datasets | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-score | FAR | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [23] | CNN-RSA | CICIDS2017 NSL-KDD | 99.99 99.23% | 99.99 99.23% | 99.99 99.23% | 99.99 99.23% | N/A N/A% | N/A N/A% |

| [35] | BMRF+RF | CICIDS2017 NSL-KDD% | 99.3 98.8% | 199.6 96.8% | 94.3 96.2% | 96.9 96.5% | N/A N/A% | 15.17 seconds 56.86 seconds% |

| [10] | GWO+RF | sCICIDS2017 NSL-KDD% | 96.25 94.64% | 96.14 95.31% | 93.75 93.14% | N/A N/A% | N/A N/A% | 50.63 seconds 40.29 seconds% |

| [32] | IG-FCBF+CNNmodels | CICIDS2017 NSL-KDD% | 99.85 99.53% | 99.85 96.77% | 99.85 97.63% | 99.85 97.13% | N/A N/A% | N/A N/A% |

| [37] | CBF+CNN-BiLSTM | CICIDS2017 NSL-KDD% | 99.53 99.40% | 99.54 99.40% | 99.53 99.40% | 99.53 99.40% | N/A N/A% | N/A N/A% |

| CICIDS2017 | 92.58 | 97.27 | 86.29 | 91.42 | N/A | N/A | ||

| [22] | BIRCH-AE | NSL-KDD | 87.88 | 89.81 | 88.05 | 88.46 | N/A | N/A |

| UNSW-NB15 | 87.61 | 97.13 | 74.20 | 81.13 | N/A | N/A | ||

| CICIDS2017 | 99.66 | 99.89 | 99.09 | 99.49 | N/A | N/A | ||

| [38] | SMOTE+CatBoost | NSL-KDD | 99.26 | 99.63 | 99.22 | 99.43 | N/A | N/A |

| UNSW-NB15 | 82.30 | 82.76 | 82.30 | 79.61 | N/A | N/A | ||

| [12] | GSWO-CatBoost | CICIDS2017 NSL-KDD% | 99.74 99.76% | 97.39 96.17% | 93.68 95.14% | 95.32 95.63% | N/A N/A% | 73 seconds 37 seconds% |

| CICIDS2017 | 99.90 | 99.90 | 99.90 | N/A | 0.10 | N/A | ||

| [21] | ML models | NSL-KDD | 97.50 | 99.10 | 95.20 | N/A | 0.60 | N/A |

| UNSW-NB15 | 98.60 | 98.20 | 97.60 | N/A | 0.09 | N/A | ||

| CICIDS2017 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0.000 | 15.3 seconds | ||

| Proposed | SAE-AM+MLP | NSL-KDD | 99.81 | 99.33 | 99.22 | 98.73 | 0.010 | 16.6 seconds |

| UNSW-NB15 | 99.83 | 98.56 | 97.84 | 98.25 | 0.019 | 13.2 seconds |

Table 7

Comparison of proposed method (SAE-AM) with other methods of multi-class classification.

| Ref. | Method+classifier | Datasets | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-score | FAR | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [23] | CNN-RSA | CICIDS2017 NSL-KDD | 99.91 99.20 | 99.91 99.15 | 99.88 99.14 | 99.91 99.20 | N/A N/A | N/A N/A |

| [36] | MHA+BiLSTM | CICIDS2017 NSL-KDD | 99.08 95.19 | 100 95 | 99 98 | 99 97 | N/A N/A | N/A N/A |

| [34] | ADASYN+LightGBM | CICIDS2017 NSL-KDD UNSW-NB15 | 99.91 92.57 85.89 | N/A N/A N/A | N/A N/A N/A | N/A N/A N/A | 0.01 6.41 14.79 | N/A N/A N/A |

| [37] | CBF+CNN-BiLSTM | CICIDS2017 NSL-KDD UNSW-NB15 | 99.53 99.40 82.30 | 99.54 99.40 82.76 | 99.53 99.40 82.30 | 99.53 99.40 79.61 | N/A N/A N/A | 118.8 seconds 71.14 seconds 127.65 seconds |

| [38] | SMOTE+CatBoost | CICIDS2017 NSL-KDD UNSW-NB15 | 99.72 99.84 98.85 | N/A N/A N/A | N/A N/A N/A | N/A N/A N/A | N/A N/A N/A | N/A N/A N/A |

| Proposed | SAE-AM+MLP | CICIDS2017 NSL-KDD UNSW-NB15 | 99.84 98.38 89.94 | 99.84 98.98 98.98 | 99.92 99.72 99.72 | 99.84 99.85 99.85 | 0.0007 0.018 0.094 | 70.4 seconds 47.8 seconds 75.8 seconds |

6.2.1. Binary Classification

The proposed SAE-AM model demonstrates outstanding performance in binary classification, achieving 100% accuracy on the CICIDS2017 dataset, indicating perfect classification of network traffic into benign and malicious categories. The model also achieved 100% precision, recall, and F1-score, highlighting its exceptional capability to correctly identify true positives while minimising false alarms, crucial for real-world applications.

On the NSL-KDD dataset, the model achieved an accuracy of 99.81%, suggesting excellent performance but indicating slight room for improvement in reducing false positives. For the UNSW-NB15 dataset, the model recorded an accuracy of 99.83%, reflecting its robust ability to distinguish between normal and malicious traffic.

In summary, the SAE-AM model showcases exceptional capabilities in binary classification across multiple datasets, positioning it as a reliable solution for network intrusion detection.

6.2.2. Multi-Class Classification

In the realm of multi-class classification, the proposed SAE-AM+MLP method was evaluated across three benchmark datasets, showcasing strong performance with some limitations in comprehensive metric reporting.

On the CICIDS2017 dataset, the model achieved an accuracy of 99.84%, and also outstanding experimental results indicating strong effectiveness in identifying different types of attacks. Additionally, the model demonstrated a very low FAR of 0.0007 and a computational time of 70.4 seconds per epoch, making it suitable for real-time applications.

For the NSL-KDD dataset, the model recorded an accuracy of 98.38%, with good performance metric results. The FAR was 0.018, with a computational time of 47.8 seconds per epoch, reflecting a balanced and efficient choice for intrusion detection. On the UNSW-NB15 dataset, the model achieved an accuracy of 89.94%, along with outstanding experimental results. The FAR was 0.094, with a computational time of 75.8 seconds per epoch, indicating a robust performance with manageable computational demands.

By employing these comprehensive evaluation criteria, the selected IDS models prove to be not only accurate and reliable but also efficient and adaptable to evolving threats.

6.3. Discussion

To justify the enhanced performance of the proposed model, we present a set of crucial design and methodological improvements.

First, the use of SAE for feature extraction enables the model to learn compact, non-redundant, and highly informative representations of network traffic. The imposed sparsity constraint ensures that only a limited number of neurons activate for any given input, helping the model to focus on the most critical patterns – especially those indicative of rare or subtle anomalies. Second, the integration of attention mechanisms – both channel and positional – enhances the model’s ability to focus on the most relevant spatial and temporal features. This targeted emphasis improves the model’s ability to distinguish between normal and anomalous traffic patterns, even in complex and high-dimensional datasets. Third, the end-to-end design of the proposed framework allows for the joint optimisation of feature extraction and classification, reducing error propagation and improving the overall learning efficiency. Unlike traditional multi-stage pipelines, this unified approach fosters synergy between components. Additionally, by adopting class imbalance handling strategies, such as data-level balancing and sparsity-aware learning, the model significantly improves its detection capability for minority attack classes – a well-known challenge in IDS.

In terms of experimental results, SAE-AM demonstrates superior performance across multiple benchmark datasets. Specifically, in the binary classification task, the model achieves 100% accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score on the CICIDS2017 dataset. For the NSL-KDD and UNSW-NB15 datasets, SAE-AM attains 99.81% and 99.83% accuracy, respectively, surpassing several recent state-of-the-art models – particularly in terms of FAR and training efficiency per epoch.

We have also provided detailed comparative performance tables – Table 6 for binary classification and Table 7 for multi-class classification – that benchmark SAE-AM against the existing methods. These comparisons clearly demonstrate the robustness, scalability, and generalisation capability of the proposed model, especially under challenging conditions involving class imbalance and complex traffic patterns. These results, combined with the carefully chosen design elements, justify the superior performance and practical applicability of SAE-AM in real-world intrusion detection scenarios.

Conclusions

The experimental results underscore the robustness and versatility of the SAE-AM methodology across various datasets and classification tasks. Achieving perfect 100% accuracy on the binary classification task of the CICIDS2017 dataset, along with high scores of 99.81% and 99.84% on the NSL-KDD and UNSW-NB15 datasets, respectively, highlights the model’s potential for applications requiring high accuracy and minimal false alarms, crucial for operational efficiency in real-world scenarios.

Key advancements, such as the selective activation of SAE with L1 regularisation, minimizes resource consumption while effectively capturing pertinent patterns essential for intrusion detection. By enforcing sparsity, the model prioritises significant features, enhancing its capability to distinguish between normal and malicious network traffic. Furthermore, the integration of a dual attention mechanism – comprising positional and channel self-attention modules – greatly improves performance. The positional self-attention module aids in understanding spatial relationships between features, while the channel self-attention module captures interactions across different feature channels, collectively enhancing detection accuracy and robustness against various intrusion scenarios.

Ablation experiments validate the model’s efficacy as a reliable and efficient solution for network intrusion detection, as evidenced by consistently low FAR. Looking ahead, future research may explore further enhancements to the SAE-AM framework, potentially integrating more advanced attention mechanisms or evaluating its applicability in real-time intrusion detection scenarios. The demonstrated capabilities of the SAE-AM methodology position are as a promising tool for bolstering network security infrastructure and effectively addressing evolving cyber threats.