1. Introduction

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are central to economic development because they provide opportunities for job creation and technological innovation [1]. SMEs continue to occupy a large proportion of economic markets across many countries, but despite their vital role, they increasingly operate within complex digital environments that expose them to heightened information risk [2]. Managing information security has therefore become a strategic necessity for SMEs, rather than a technical option because of these unique challenges.

Unlike many large organisations, SMEs lack financial resources, institutional capacity, and the necessary skills to implement comprehensive and structured information security controls when processing data. Scholars suggest that SMEs may overcome some of these challenges by adopting advanced technologies, such as big data analytics despite their small size, to remain competitive and secure their data more effectively [3]. In South Africa, where this study is domiciled, SMEs’ processing of data and personal information is regulated by the Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA) No. 4 of 2013 [4]. POPIA regulates the collection, processing, sharing, and use of personal information held by businesses. POPIA outlines eight fundamental principles regarding lawful data processing. These eight include accountability, processing limitation, purpose specification, further processing limitation, information quality, openness, security safeguards, and data subject participation [5]. POPIA closely aligns with international data

security and protection standards, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) of the European Union (EU), although GDPR has a wider reach to more countries than POPIA. Regarding data breaches, GDPR, unlike POPIA, has ‘a clear seventy-two hour notification requirement, implements higher, monetary fines, requires privacy by design and impact assessments, and allows for data portability’ [6]. Stakeholders and employees of SMEs expect that personal information is to be processed in line with POPIA regulations. These expectations may present unique challenges for SMEs, which must balance regulatory obligations with their own limited resources.

1.1. A Call for Regional-Specific Models to Address Unique SME Challenges

There are ways that SMEs can detect network intrusions and network traffic anomalies, such as data mining, statistical analysis, artificial intelligence (AI), neural networks, and Markov modelling [7]. Some SMEs apply these techniques and approach to know how they can secure their networks, but many often lack the resources and dedicated cybersecurity expertise to implement these information security measures. This leaves them vulnerable to threats. The lack of resources has been cited as a crucial challenge that SMEs face in protecting and securing their networked information assets [8]. SMEs also lack experience and knowledge, face high risk, and outdated or limited security procedures [9] while struggling with regulatory compliance [10]. Existing information security network models specific to these SMEs operating in South Africa often fail to address unique constraints and how to overcome these challenges. A tailored approach is therefore necessary for South Africa’s SMEs to retain information security resilience. The conundrum is that the current information security threats on SME networks are existential, meaning that the impact and repercussions on business continuity are adverse in the advent of network attacks.

1.2. Research Objectives

This study, therefore, aims to develop a grounded theory (GT) that reflects South Africa’s constraints. This theory is to be developed using a GT approach. Responding to prior calls for contextualising cybersecurity theories [11] the research seeks to:

identify, through practitioners’ lived experiences, the existing information and network security practices adopted by SMEs; and

develop a GT that is pragmatic to South Africa’s unique contexts and challenges that articulates SMEs’ response to security threats.

The subsequent sections are structured as follows. The literature review addresses the present challenges of information security for SME networks and situates the study within current debates on SMEs cybersecurity concerns in safeguarding network infrastructure. The research methodology section that follows the literature review elaborates on the methods used to elicit qualitative data using the GT method. The data analysis is explained in the section following the research methodology. Discussions and conclusions of the research follow afterward.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Information Security on SME Network Infrastructure

Information security within the existing network infrastructure safeguards SME data traversing the Internet from leakage, damage, or misuse while ensuring business continuity and credibility [12]. The foundational model that underpins information security efforts is the confidentiality, integrity, and availability (CIA) triad, a well-established baseline that guides SMEs in implementing effective internal network security control measures [13]. According to Pawar and Palivela [14], SMEs in different business domains have different priorities when applying the CIA triad to their information security efforts. Pawar and Palivela [14] provide an example of this domain difference shown in Table 1.

Table 1

An example of SME domain and CIA triad prioritisation.

Table 1 underscores the contextual nature of information security in SMEs. SMEs in banking may prioritise confidentiality, SMEs in e-commerce may emphasis availability, while SMEs in the pharmaceutical industry may be more concerned with integrity. Different contextual applications of the CIA triad highlights that no single universal model may adequality fit SMEs across different sectors.

Emerging studies suggest that due to rapid digitalisation in SMEs, and in particular through Industry 4.0 technologies, SMEs exposure to cybersecurity risk and security challenges have been heightened [8]. As digital systems integrate across SME supply chains, SME network dependencies increase, amplifying the consequences of cybersecurity breaches. Many concerns have been raised about the insufficient governmental and institutional support for SMEs adopting these advanced secure technologies [10], the uneven application of information security metrics [16], and, importantly, the promising exploration of cutting-edge AI-based threat intelligence in SMEs [17].

2.2. Unique Contexts in South Africa that Shape Information Security on Network Infrastructure

South African SMEs recognise the transformative impact of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) on digitising their network infrastructure [8]. The Presidential Commission on Fourth Industrial Revolution (PC4IR), appointed in April 2019, was tasked to develop a 4IR strategy as a clear priority for shaping innovative technologies for safe use in businesses through a policy framework [18]. South Africa is generally ranked as among the leading countries in Africa in information and communication technology (ICT) governance due to its establishment of favourable policies. However, it faces criticism that many of these good policies largely remain unimplemented [18]. In 2024, according to the World Economic Forum’s Network Readiness Index (NRI), South Africa was ranked 72nd out of 133 economies. Mauritius led in Africa (ranked 60th), followed by Seychelles (ranked 71st). The NRI assesses the application and impact of ICTs in terms of leveraging opportunities. As Hadzic pointed out, South Africa faces income inequalities, high mobile tariffs, and inconsistent policy priorities [18]. He gives an example of the National Integrated ICT Policy White Paper 11, finalised in 2016 and accepted by the cabinet and parliament, which focused on improving the inclusion of all citizens in the digital economy. However, not much of the White Paper has been implemented. He further contends that the uptake of 4IR in South Africa has been impeded by limited proficiency in 4IR technologies and amplified inequalities, inadequate supporting infrastructure, and a lack of active engagement from stakeholders, who develop digital policies in siloes instead of an integrated approach [18]. Chidukwani et al. [19] have pointed out that skills are necessary for SMEs to prioritise their network infrastructure information security initiatives. Moreover, a concern in the financial sector is the lack of consistent implementation of policy and regulatory models for proper and secure ICT usage in the advent of 4IR technologies. For SMEs, this is crucial since many face the daunting task of compliance requirements within prescripts of relevant laws to avoid legal risks and fines [20]. The lack of inconsistent policy implementation has led to many challenges, such as cyber fraud.

The growth in cyber fraud incidents has been detrimental to SMEs’ profitability, reputation, and goodwill [21]. As 4IR diffuses into South African businesses, SMEs will continue to face cyber fraud similarly to their larger financial sector counterparts, since these kinds of crimes encompass a wide range of Internet-enabled illegal activities that potentially target personal or business network infrastructure for fraud perpetration using techniques such as ransomware attacks, phishing, card skimming, SQL injections, distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, and business email compromise [22]. Cyber fraud has cost South African businesses close to R2.2 billion a year [21]. As pointed our earlier, for SMEs within the banking and financial domain, the crucial network security priority would be the confidentiality of information against these forms of innovative attacks on network infrastructure. This can be contrasted with those SMEs operating, for example, in the e-commerce domain, where these would prioritise availability as the crucial information security mitigating initiative. Khan et al. [15] suggest that SMEs in the pharmaceutical domain might focus more on integrity as a network information security priority.

South African SMEs are therefore tasked to robustly safeguard their network infrastructure to mitigate against these information security risks. Implementing information security measures in their network infrastructure requires safeguarding the Internet protocol (IP) and transmission control protocol (TCP), commonly known as TCP/IP, as the most vulnerable two points of experiencing many cyberattacks that often threaten SME information assets [7]. Cyberattacks can occur by injecting malicious packets into the TCP/IP protocol to compromise data integrity, confidentiality, and availability. Therefore, information security around TCP/IP networks is essential for safeguarding information assets from intrusion, a challenge that many SMEs struggle to address [16]. A review of the information security threats to SME infrastructure is shown in Table 2.

Table 2

Information security threats on SME network infrastructure.

| Information security attacks on SMEs | Thematic area | Author |

|---|---|---|

| Ransomware | 71% of SMEs experienced ransomware attacks in 2021. The cost of resolving the attack was R6.4 million. | Mugwagwa et al. [23] |

| Phishing | Phishing attacks were noted as an entry point to other intrusions. | Cornelius et al. [24] |

| Card skimming | The escalation of skimming, with a drastic expansion. | Budhram [25] |

| SQL injections | SMEs have experienced SQL injection attacks, which are now more sophisticated due to the use of AI. | Alghawazi et al. [26] |

| Insider threats | Intrusion attacks emanating from insiders, constituting a threat to client information. | Njowa et al. [27] |

| DDoS attacks | Remote working (caused by the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns) lacked the added network layer of cybersecurity defence causing a sharp rise in DDoS attacks. | Mutemwa et al. [28] |

As shown in Table 2, SMEs in South Africa continue to face various information security attacks, with each type of attack contributing to the growing concerns over the safety of their network infrastructure. Ransomware attacks have been notably prevalent and reported to have affected 71% of SMEs, resulting in a significant financial burden of R6.4 million to resolve the attacks [23]. Phishing attacks and social engineering are more common and serve as an entry point for other more nefarious and advanced forms of intrusions [24, 29]. Card skimming has escalated, with SMEs experiencing a drastic expansion [25]. Due to advancements in the use of AI and large language models, the nature and form of SQL injection attacks have shifted and have become more sophisticated, making these kinds of attacks more challenging for SMEs to defend [26]. Insiders (employees within SMEs) also remain a significant concern, since they are familiar with business operations and can initiate attacks within that can threaten client information [27]. Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks are also common and proliferated at the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns, where remote work was common. The challenge was that remote work lacked the additional network security layer of cybersecurity defence necessary to keep businesses safe.

2.3. Emerging Trends in Information Security for Network Infrastructure

Globally, information security is undergoing a paradigm shift driven by automation AI, and machine learning (ML) [30, 31]. SMEs lack the necessary skills to be able to keep pace with the paradigm shift, formulate clear information security policies to secure their networks, plan for disruption, or even clarify their diverse information security goals [32]. The information security around network infrastructure is constantly evolving, with many new approaches, tools, and technologies emerging to address the ever-changing security threats [33]. AI and ML can now be used to automate threat detection and respond appropriately, and this may reduce the need for extensive in-house skills. According to Varma et al. [17], AI and ML enable SMEs to detect and respond to threats more efficiently by analysing vast datasets for patterns and anomalies. This proactive approach enhances the SMEs’ network security position. With AI initiatives taking root in SMEs, network security automation and orchestration that now uses ML operations (MLOps) can enhance network security responsiveness through vulnerability scanning, log analysis, and incident response [34]. There are also emerging information security tools embedded with intuitive interfaces that enable less skilled employees to manage security settings by simplifying the often-complex security configurations, making it easier for SMEs to implement necessary security and protection. New models and approaches, such as zero-trust architecture, are becoming more popular. As Rose et al. [35] emphasises, a zero-trust architecture’s ‘never trust, always verify’ principle aligns with the evolving threat landscape, where traditional perimeter-based defences are no longer sufficient. Pavana and Prasad [36] consider zero-trust security models as shifting the focus of securing network infrastructure from perimeter defence to the granular control and monitoring of users and devices. SMEs are, therefore, beginning to recognise the need to authenticate and authorise every user and device trying to access their networks [37]. The next section explains the methodology used in the research to gain the lived experience of network security practitioners within the various SME domains.

3. Methodology

This research was qualitative and applied the GT method espoused by Glaser and Strauss [38] that the researchers believed would be the most suitable for studying the lived experiences of network security practitioners and the technologies used in network security management. The qualitative research approach is considered non-liner, and will often be recursive, meaning that as the researchers collect information, they may notice new and emerging ideas or patterns, and may be required to reflect further by going back to old data and re-analysing such data again.

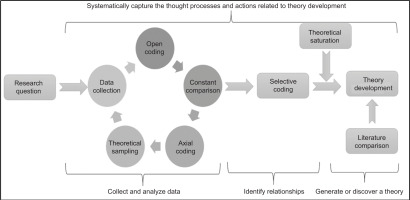

The choice of qualitative GT approach to this work is important because of the relative complexity of network security management within SMEs. There may not be sufficient theories to explain these complexities. The GT method presented by Glaser and Strauss [38] was seen as capable of forming a theory from lived experiences, which could explain these complexities, using exploratory qualitative research [39]. Cho and Lee [40] believe that the GT method is suitable for integrating diverse qualitative data sources and extracting their core concepts and relationships. The GT method encourages step-by-step comparisons and in-depth data analysis to form deep theories [41]. The coding process of the GT method is a systematic exploration and sorting process, from open coding to selective coding, where a deep theoretical model is gradually constructed. In the initial phase, researchers perform open-ended coding by carefully reading and iteratively analysing qualitative raw data, identifying key concepts and patterns, and using the participants’ exact words. Pidgeon and Henwood [42] point out that the GT method can help combine existing theories and new concepts to deepen, verify, revise, and expand on the existing theories and construct theoretical models applicable to actual situations. During the validation and revision process, researchers bring new theoretical models back to the data to ensure the practical applicability and feasibility of the models [43]. The GT method emphasises the close connection between theory and practice in practical application. The GT method process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Elements of the GT method and strategies for enhancing rigor. Source: Corbin and Strauss [44].

The explanation of the steps in Figure 1 is as follows.

3.1. Data Collection

Ethical clearance was obtained before interviews with eight identified network security practitioners. This methodological criterion prioritised the conceptual depth that these eight provided over sample size. A theoretical sampling approach justified the selection of these eight and is discussed in detail in the sections that follow. This approach was considered appropriate for accessing a specialised population of SME network security practitioners within the Gauteng province of South Africa, with the majority coming from Johannesburg, which is the financial capital of South Africa. When collecting data on the network security management of SMEs through interviews, researchers ensured that the interview process fully respected the privacy and confidentiality of the respondents. Following on Lincoln and Guba [45] who provide the criteria for trustworthiness, during the interview process, the researchers upheld credibility by allowing the interviewees to confirm through careful documentation their responses to the interviews. The interviews were carefully transcribed to preserve crucial details with the interview protocols being followed in this process. Researchers also maintained a neutral and open attitude and encouraged the network security practitioners to share their practical lived experiences and perspectives while avoiding leading questions. Consent forms were obtained from all the participants. The procedural rigor in data collection ensured the dependability and authenticity of the qualitative dataset that would form the basis for the subsequent substantive theory to be developed.

3.2. Open Coding

Open coding can be considered as the initial stage of qualitative data analysis and will involve analysing and classifying the raw data to identify the key concepts and categories from emerging patterns. The researchers subdivided the transcribed qualitative data into smaller parts and assigned descriptive labels or nouns, called ‘open codes’ to each part to reflect the content. This helped the researchers to organise complex data into meaningful concepts and finally categories (which provided the basis for theoretical construction). Open coding involved using the codes derived from the transcripts known as emergent codes. There has been a debate regarding how exactly this is to be done. In the Galserian approach, Glaser [46] suggested that this should be done line-by-line, while in the Straussian approach, Corbin and Strauss [44] encourage researchers to code ‘conceptually similar events/actions/interactions as a way of generating a participant-generated “theory” from the data’.

Following on Corbin and Strauss [44], the process of open coding was carried out by identifying conceptually similar interactions, from the transcripts of interviewees, to uncover initial codes (labels or nouns) and concepts that captured network security participants’ actions, interactions, and strategies for handling network threats. The open codes obtained from open coding process were then clustered into concepts such as ‘strategy & policies’ and ‘resource/budget’, which were then clustered into higher level categories to form, for example, the category ‘governance and strategy’ that emerged from these concepts. The higher-level categories would later form the conceptual foundation of the substantive theory.

3.3. Constant Comparison

The constant comparison step is a technique created by Glaser and Strauss [38] where the researchers classified and integrated pieces of raw data based on their characteristics and constructed the classifications from incidents they observed in an orderly manner to form new theoretical perspectives [47]. This constant comparison of the incidents began to generate theoretical properties that would form the basis for generating categories. In the process of comparisons, the researchers thought of the many possible range and types or continua of the categories that could be created, including the dimensions, the conditions under which the incidents were observed, and the consequences of these incidents, in relation to other incidents. The constant comparison of these incidents started generating theoretical properties of the mentioned categories.

This step was crucial to substantive theory-building because through repeated comparison and coding of the data the researchers were able to uncover patterns, concepts, and categories [40]. Conceptually similar events were compared with previously coded data to refine category boundaries and identify relationships between them. As Charmaz [48] points out, the constant comparison approach is important in ensuring that the categories that emerge from this comparison will remain grounded in empirical reality, rather than in what is known as abstract theorising. This constant comparison of codes to codes, codes to categories, and categories to categories enhances the validity of the emergent substantive theory.

3.4. Axial Coding

In the axial coding step, researchers further organised the concepts in the open coding step to reveal the relationships, patterns, and connections between the concepts. Researchers selected the core concepts as connection points and then, through in-depth analysis and the arrangement of each concept in the open coding, revealed the relationships, interactions, and logical levels between them [49]. As suggested by Corbin and Strauss [44], the axial coding process involved identifying relationships and interactions between causal conditions (e.g. limited security awareness), contextual conditions (e.g. the unique South Africa’s SME resource constraints), and intervening conditions (e.g. the innovative AI-driven incident response systems). The outcome of axial coding was a network of interrelated categories that illustrated how SMEs adaptively build resilience in their network security systems.

3.5. Selective Coding

The selective coding step was an important final step in GT method that helped the researchers analyse in-depth and selectively focus on the most representative and important concepts in open coding to build a more detailed theoretical model. During this final phase, the researchers identified a single and central category (core category), in this case the ‘trust-integrated security resilience’, which emerged and integrated all other categories earlier developed in the open and axial coding phase. The other categories were linked to this single and central category, and the relationships among categories were refined.

To develop this core category, theoretical memos were continuously written so that a coherent storyline could be formed [50]. Arriving at this coherent storyline was momentous, seeing that the elements appeared to align and form a cohesive understanding. It is from this understanding that the GT was systematically developed from the ground up, such that a theory could be explained succinctly in a few strong sentences. From this understanding also, it meant that the data analysis had successfully captured the essence of network security resilience in SMEs in a form of theory.

3.6. Theoretical Sampling

Theoretical sampling is a keymethod in GT research [38], and is not to be seen as purposeful sampling. As Hood [51, p. 158] suggests ‘all theoretical sampling is purposeful, but not all purposeful sampling is theoretical’. Purposeful sampling is considered as a sampling approach that selects participants who have a shared knowledge or experience of the particular phenomena to which the researchers may identify as a potential area for study [52]. In contrast, as Morse [53] explains, in theoretical sampling,

the selection of participants and perhaps what is most important, the reasons that underpin that selection, will vary in accordance with the theoretical needs stipulated by the study at any given time, pointing out that when researchers use theoretical sampling, they cannot know in advance precisely what to sample for and where it will lead.

Glaser [46, p. 37] makes theoretical sampling purpose-driven for the main purpose of refining the emerging theory. Therefore, theoretical sampling progressively selects participants according to emerging theoretical insights in reference to the emerging theory, thereby supporting developing and deepening new theoretical constructs, rather than seeking statistical representativeness.

In this research, theoretical sampling guided the decision of whether to conduct additional interviews with network security participants and SME managers or not. From the researcher’s perspective, each round of data collection was purposefully informed by the need to elaborate, saturate, or refine specific theoretical dimensions [48]. When succeeding interviews failed to generate new conceptual properties or relationships, and participants would reiterate what was already known, the decision was made to cease data collection, indicating that theoretical saturation for specific dimensions had been reached.

3.7. Theoretical Saturation

Theoretical saturation is a key concept in qualitative research, particularly in the GT method. It refers to the point in the data collection and analysis when the new data elicited from study participants no longer yields additional insights or information about a specific phenomenon or concept [41]. When theoretical saturation is reached, data collected is deemed sufficient to fully explain a particular aspect of the study, and further data collection becomes redundant. In this research, theoretical saturation was reached after eight interviews were concluded. This was because no new properties or relationships were emerging in the categories. After saturation, the developed substantive theory was considered conceptually rich and empirically stable, consistent with the guidelines of Saunders et al. [54].

3.8. Theory Development

Since the GT method is an inductive approach based on the collected data, the theory to be developed from the steps explained above was based on the concepts and categorisation to ultimately come up with a theory that could explain network security management in SMEs [40]. The researchers maintained a flexible and iterative approach throughout the theory development step, allowing theory development to emerge from the data, rather than imposing pre-conceived ideas [38]. The final emergent model, called the Theory of Information Security Resilience for SME Network Infrastructure (TISRI), represents a dynamic and context-sensitive framework that illustrates how SMEs co-evolve their capacity, trust mechanisms, and AI-driven systems to achieve network resilience. We discuss its development in Section 4.3. The inductive process ensured that TISRI was innovative, grounded in practitioner experience, and responsive to the realities of cybersecurity governance in the South African SME sector.

4. Data Analysis and Findings

4.1. Ethics

The researchers adhered to ethics regarding how the research participants were contacted and how data was elicited using an interview schedule, transcribed, and analysed. The researchers were also guided by ethical principles of participants’ rights to provide data and how the data was to be used. The research was granted ethical clearance by [name withheld for blind peer review]. The study was approved and granted an approval number [withheld for blind review]. Participants were required to give their oral informed consent to participate, and this was recorded. The consent included the following:

Participants would be required to agree to take part in the interview.

Participants were free to stop the interview process at any time they felt uncomfortable with the line of questions.

Participants were assured anonymity during and after the interview.

Table 3 provides a comprehensive profile of the participants who participated in this study. It covers their basic information, including gender and their role in their respective organisations.

Table 3

Profile of the participants.

4.2. Coding and Categorisation

This section details the process of coding and classifying interview data. In the coding and categorisation steps, five categories were derived from eight concepts, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4

Concepts, categories and theory development.

Each category is described in detail based on live experiences of the study participants as follows.

4.2.1. Category: Governance and Strategy and Policy Integration

The category ‘governance and strategy’ was derived from the concepts ‘Strategy & Policies’ and ‘Resource/Budget’. The following narrative elaborates on these concepts.

4.2.1.1. Strategy and Policies

The SMEs network security strategy was guided by a holistic and integrated approach, as P02 noted, emphasising the importance of a comprehensive and integrated security stance. P02 stressed the crucial role of risk assessment stating: ‘And this holistic approach,CD37 I think, just puts us on the right path regarding security. Risk assessmentsCD38 are crucial to us as a company… I believe that risk assessment is the foundation for building a strong network security strategy’.

This observation suggests that effective governance within SMEs requires the integration of risk assessment into strategy formulation, and continuous improvement cycles. Such a holistic strategy would ensure alignment between technology, policy, and organisational objectives with risk assessment, therefore complying with standards such as ISO/IEC 27001 that emphasise embedding risk assessment within strategic planning. P02 emphasis on a ‘holistic’ and ‘integrated’ strategies reinforces the need to merge compliance-driven governance with adaptive and context-specific policy development.

4.2.1.2. Resource/Budget

Resource limitations and budget constraints emerged as key challenges faced by many SMEs in securing their networks, as P02 highlighted: ‘The first thing that jumps out is resource limitationsCD28… Many SMEs cannot allocate enough funds [budget constraints]CD29 towards advanced security solutions… Budget constraints mean we often run on older systems...’.

Similarly, P08 echoed this concern, emphasising the impact of a limited budget on the SME’s technological infrastructure: ‘A limited budget [budget constraints] is a big problem in SMEs… Our strategy involves a mix of in-house efforts and outsourcing [In-house Outsourcing]CD30’.

P02’s insights highlight a persistent information security governance challenge in South African SMEs, namely that financial resource constraints prevent adequate investment in modern information security tools and skilled personnel. Consequently, Many SMEs resort to hybrid approaches that rely on non-uniform, ad hoc and often ill-informed outsourcing arrangements from information security service providers. This ‘resource bricolage’ may temporarily sustain operational functionality, but in the long term it proves costly and undermines organisational resilience.

4.2.2. Category: Adaptive Security Infrastructure

The category ‘Operational Measures’ was derived from the concepts ‘access control’ and ‘tools & infrastructure.’ The following narrative elaborates on these concepts.

4.2.2.1. Access Control

SMEs implemented several key practices and measures to strengthen their network security posture. Participants emphasised the significance of multi-factor authentication (MFA), with P02 stating: ‘MFA [multi-factor authentication]CD1 is also something that is important’.

For enhanced network information security, many SMEs expressed a growing commitment to improving access control mechanisms, particularly through two-factor authentication (2FA), as emphasised by P03:

Besides the usual anti-viruses and firewalls, we enforce two-factor authenticationCD2… We have also been strict about password policies,CD3 so strong and unique passwords are changed periodically… I think the SMEs need to focus on basic password policies.

P03’s statement illustrates that SMEs are beginning to institutionalise foundational access controls, such as 2FA and strong password management regimes. These controls align with layered defence models, such as those proposed in NIST SP 800-63B. However, P03’s observation that ‘SMEs need to focus on basic password policies’, indicates that many SMEs still fall short of deploying advanced access control mechanisms, including centralised identity management or zero-trust architectures, which extend beyond the basic password enforcement.

4.2.2.2. Tools and Infrastructure

Network security remained a top priority for SMEs, with encryption emerging as a pivotal safeguard tool. As P02 emphasised: ‘Well, for my company, encryptionCD7 is important, especially with all the customer data flowing around within the organisation’.

This highlights the central role that encryption plays in protecting the vast amount of customer data managed by SMEs. The sentiment is echoed by P04, who noted the following:

We are also using data encryption, especially for sensitive company data… And as data encryption. If a hacker, by some chance, intrudes sensitive data, they should not be able to read the data without the encryption key.

The observations of P02 and P03 highlight encryption as a fundamental control measure that promotes both data privacy and regulatory compliance, particularly in relation to South Africa’s POPIA Act [6]. Furthermore, from P02 and P03’s assessment, SME encryption practices were observed to be systemic and ‘important’, reflecting growing SME awareness of the role encryption played in data confidentiality and maintaining trust.

4.2.2.3. Category: Culture

The category ‘culture’ was derived from one concept, ‘culture’. P02 highlighted that network security had become a core business priority, stating: ‘I believe it is a core business priority at this point. [importance of security]CD15 … every enterprise, no matter what size they are, must have network security management in place’.

Similarly, P01 recognised that cultivating a strong information security culture was pivotal to meeting SME network security demands, emphasising ‘the whole idea is to build a culture that surrounds the security’.

As P01 elaborated further on the broader implications of promoting information security culture:

Protecting not just the data but also the company’s very reputation and trust of our clients [reputation and trust]CD17… It is about trust, business continuity, and ensuring proper customer experience… Effective network security is not just about defence but about ensuring the long-term business and preserving stakeholder trust.

The findings of P02 suggest that SMEs are increasingly embedding information security within their organisational culture, acknowledging it as a strategic enabler, rather than merely a compliance requirement. As demonstrated by P01, a robust information security culture, supported by effective leadership commitment and management engagement, helps SMEs sustain ‘long-term business [sustainability] and preserve stakeholder trust’.

Furthermore, P01’s assertion that ‘the whole idea is to build a culture that surrounds the security’ points to the understanding of the shared responsibilities culture which fosters behavioural resilience among employees. This shared responsibility reflects the notion that information security awareness and actions are collective obligations, forming part of the SME’s identity, rather than an external imposition or requirement.

4.2.3. Category: Capacity-Building and Skills Development

The category ‘training and collaboration’ was derived from two concepts: ‘training’ and ‘collaboration.’ The following narrative elaborates these concepts:

4.2.3.1. Training

Employee training and awareness constitute SMEs’ network security strategy. As P01 emphasised, training was necessary due to the ever-evolving nature of network security threats: ‘... one of the first things we prioritised was employee trainingCD18 … One thing we have realised is the importance of continuous employee training. Employee training has become a regular feature’.

P01 pointed out that SMEs need to go beyond informal, once-off training to more structured and ongoing cybersecurity awareness programs tailored to SME-specific contexts. This type of SME resilience therefore requires periodic training that should be tied to performance metrics.

4.2.3.2. Collaboration

Effective communication plays a pivotal role in pursuing a comprehensive network security strategy. Active communication among the IT staff is a core element, as emphasised by P02, who noted that recognising the importance of seamless information exchange within the IT team: ‘Our ongoing related strategies also include active communicationCD24 among the IT staff… It is also important that certain stakeholders are communicated with [stakeholder communication]CD25 and are aware of the risks…’.

P02 underlines the collaborative nature of information security governance, where SMEs’ internal operations are coordinated with external partners and regulators. From our interpretations, collaboration and information-sharing was observed to be important towards improving SMEs’ own awareness of security posture and incident response agility and as pointed out to be made ‘aware of the risks’.

4.2.4. Category: Network Security Incident Management

The category ‘Network Security Incident Management’ was derived from three concepts: ‘incident response,’ ‘miscellaneous challenges’, and ‘monitoring.’ The following narrative elaborates on these concepts.

4.2.4.1. Incident Response

Effective incident response is a vital component of any network security strategy. P02 shared their approach, highlighting the importance of swift communication and action when an incident occurs: ‘The immediate response is to alert our IT department, or they alert us, depending on whoever identifies the incident first [incident response]CD33… I think every SME also needs a clear incident response planCD34’.

P02’s observation resonates with global best practices, such as NIST 800-94 [55], which addresses early detection of information security incidents while proposing clear escalation paths, and guidelines for post-incident analysis. P02 articulates this well by suggesting that ‘every SME also needs a clear incident response plan’.

4.2..4.2. Miscellaneous Challenges

In addition to the risk network security that vendors had on SMEs, the impact of digital transformation also constituted part of the many challenges SMEs were observed to be facing. As pointed out by P01, these risks posed a significant challenge:

And also, because digital transformation is becoming more popular, they are becoming more reliant on IT systems, online procedures, things like that [digital transformation impact]CD42. Also, vendor riskCD43 is challenging. SMEs heavily rely on third parties… Our company works with third parties, so we focus more on vendor risk management.

This observation situates SMEs at the crossroads of digital transformation and cybersecurity, pointing out that as SMEs get more involved with vendor and third parties. Information security risks often cascade into SMEs operations due to shared infrastructure and lack of contractual oversight. This risk is pointed out by P01 showing that SMEs manage this by focusing ‘more on vendor risk management’.

4.2.4.3. Monitoring

P03 highlighted the importance of monitoring network security threats and staying alert, and illustrated this commitment to continuous monitoring by stating:

And to stay alert on threats, we also use ThreatConnect [threat monitoring]CD47. We cannot afford any breaches, especially with client data, so constant network monitoringCD48… They are always on alert, monitoring traffic and ensuring our firewalls are up to date [continuous monitoring]CD49.

Technologies such as Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS) support continuous monitoring and vigilance. This was pointed out by P08, who explained as follows: ‘And the technique we use is the IDS to monitor our network [IDS monitoring]CD50 for malicious activities. ... threat intelligenceCD51 is very important’.

Observations from P03 and P08 indicate that monitoring of information security incidents is a crucial mechanism for SMEs to maintain technical vigilance, particularly in ‘ensuring firewalls are up to date’. This aligns with the suggestion by Falkner and Hiebl [56], who note that the resources and characteristics of SME owners have a significant impact on their risk management processes. As observed, SMEs are shifting from reactive monitoring practices to adopting a more predictive approach in threat intelligence.

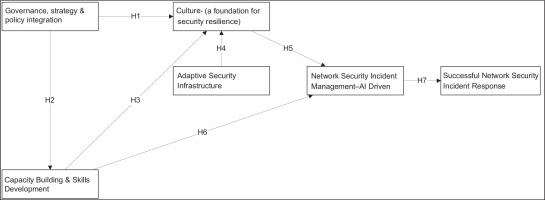

4.3. Substantive Theory Development

The categories governance and strategy, operational measures, culture, training, and collaboration, and network security incident management were further developed by constant comparison with codes and literature to discover what patterns were emerging and how a theory was developing. This process, called continuous comparative analysis, requires digging deeper into the relationships between the data to formulate new grounded theories. Glaser et al. [57] have shown that these categories must be adjusted to accommodate the higher abstraction levels. This adjustment is part of the theory-building process to ensure that the theory remains applicable and accurate in explaining and describing phenomena. By paying close attention to emerging trends and patterns in the data, the researchers developed the substantive theory, presented in Figure 2.

The substantive theory presents constructs that emerged inductively, rather than being imposed from an existing model. This approach of theory development is consistent with GT logic, and is an innovative way of integrating governance, culture, capacity-building and adaptive infrastructure as interdependent enablers of AI-driven network security incident management. The theory, known as TISRI, reconceptualises network security as a dynamic socio-technical process, rather than a purely technical function. TISRI is seen as a process model leading towards the outcome: successful network security incident response. The five core categories of TISRI, and the pathways illustrated (H1–H7), depict how governance and policy integration shape a culture of resilience, ultimately building driving effective network security management of SMEs and successful response outcomes. Therefore, SMEs are encouraged to take management measures to help enterprises improve their network security.

4.4. Summary of Hypotheses for the Substantive Theory – TISRI

H1: Governance, strategy, and policy integration will influence SME culture.

H2: Governance, strategy, and policy integration will influence SME capacity-building and skills development.

H3: Capacity-building and skills development will influence culture.

H4: Adaptive security infrastructure will influence culture.

H5: Culture will influence network security incident management.

H6: Capacity-building and skills development will influence network security incident management.

H7: Network security incident management will influence successful network security incident response.

5. Discussion

Theory of Information Security Resilience for SME Network Infrastructure, developed using the GT approach, proposes that managers prioritise establishing clear governance and strategic planning efforts related to network security. This theory is innovative and considers the unique SA constraints that are important to information security management by reflecting real-world SME management practices.

Conceptually, TISRI offers a taxonomy of SME security management approaches that form part of this study’s contribution and are actionable for policymakers and IT practitioners. Policymakers and IT practitioners can now understand and position ‘culture’ as the foundational mechanism which links governance and adaptive infrastructure. TISRI can now frame resilience as an emergent property of socio-technical alignment, rather than as a static organisational capability. TISRI can be contrasted with other linear or compliance-based security theories, which may not show how capacity-building and AI-driven incident management co-evolve to strengthen organisational responsiveness to network threats. For example, on one hand, models such as information security management lifecycle (ISO/IEC 27001 model), Von Solms and Von Solms (2004), Information Security Governance Model, or Whitman and Mattord (2005) Security Lifecycle Model, focus on policy compliance, hierarchical governance, and control maturity, and depict security as a sequence. TISRI, on the other hand, departs from these by embedding continuous learning and feedback. TISRI also emphasises non-linear development, such as culture and capacity-building which can both catalyse rapid adaptation without necessarily going into sequential maturity steps proposed by, for example, Whitman and Mattord’s (2005) security lifecycle model. TISRI also shifts from defensive logic to resilient adaptability, meaning that the theory integrates trust and human capacity as proactive dimensions of information security.

Methodologically, TISRI is grounded in empirical narratives, revealing previous untheorised insights such as the role of culture as a mediator and influencer of adaptive infrastructure. The taxonomy drawn from the substantive theory is mapped with theoretical considerations that SMEs can apply. This is shown in Table 5.

Table 5

Taxonomy and theoretical considerations.

5.1. Governance, Strategy, and Policy Integration

The study has shown that fragmentation is a major limitation in SME information security governance and strategic imperatives to securing information assets. South African SMEs do not have formal information security policies or structured governance mechanisms [58]. Many of these SMEs use or derive policies that have been developed in silos. This is because SMEs lack the capacity to coordinate their efforts between themselves and other regulatory bodies, technology providers, or industry stakeholders. TISRI places emphasis on an integrated and aligned approach to imperatives for policy development by introducing mechanisms that encourage stakeholder participation. This means that SMEs can use it as a guide to ensure that their use of emerging technologies for information security aligns with regulation. In doing so, TISRI shifts SMEs from compliance-driven policy adherence towards strategic integration of governance and this leads to resilience.

5.2. Capacity-Building and Skills Development

To improve skills and expertise for SMEs in the age of 4IR, which has made them vulnerable to sophisticated cyber threats such as AI-driven phishing and ransomware attacks, new training approaches to be considered may include modular online learning, peer-to-peer cybersecurity networks, vendor-supported certification schemes, and partnerships with local universities or managed security providers. SMEs can be sensitised to incorporate these structured capacity-building initiatives that would aim at building on local skills. These initiatives should be accessible and cost-effective to strengthen their information security posture. Furthermore, it is important that the training content be contextualised to local South African SME operations, placing emphasis on low-cost cyber hygiene, social-engineering awareness, and leadership commitment. Embedding capacity-building into everyday operations, SMEs can progressively increase cybersecurity maturity and possibly avoid dependency on costly external expertise.

5.3. Adaptive Security Infrastructure

Small and medium-sized enterprises do not adequately respond to new models for building robust cybersecurity infrastructures, and this limitation is compounded by high mobile data costs and unreliable Internet connectivity predominant in South Africa. Research has shown that South African SMEs are restricted by bandwidth constraints and high data tariffs [59], forcing many to rely on fragmented tools or outdated security control measures that are not unified or scalable. TISRI provides insights that can guide SMEs to consider adaptive security infrastructure that is scalable, AI-driven security solutions that can address South African needs for these SMEs to remain resilient. TISRI’s adaptive infrastructure may in this context refer to scalable, modular, and AI-enhanced systems capable of dynamically adjusting to changing threat landscapes. Such an infrastructure may help SMEs optimise their limited resources. TISRI can provide insights on how integrating threat-intelligence sharing networks may overcome infrastructural challenges in an adaptive rather than static approach. This way SMEs may be able to maintain effective protection even during connectivity, problems faced in South Africa, or cost limitations.

5.4. Culture – Foundation for Security Resilience

Forming and encouraging a strong information security culture would be a good starting point for the successful implementation of information security policies. Several industry reports support this observation and opine that ‘people, not firewalls’ are the greatest vulnerability to cybersecurity that are faced by SMEs. As such SMEs must foster cultural of transformation, rather than continually adopting reactionary technical fixes. TISRI positions SME culture as a central driver of desirable information security behaviour shaped by good governance, skills development, and a robust and adaptive security infrastructure. SMEs should foster a culture that mediates governance structures, training, and technology, thereby encouraging good information security practices which translate into secure everyday behaviour. This good behaviour may include responsible data handling, incident reporting, and compliance with information security practices. A culture of information security awareness is necessary to enhance employee compliance with information security policies, thereby reducing insider threats and improving the overall cybersecurity resilience. SMEs should be careful to note that sustaining a good information security culture requires ongoing reinforcement through leadership modelling. Other approaches which can encourage and sustain good information security culture would include periodic simulations and promoting open communication that normalise discussion of cyber risks. By treating information security culture as a living system, rather than a one-off intervention, SMEs can build resilience.

5.5. Network Security Incident Management – AI Driven

Small and medium-sized enterprises lack network incident response approaches that require a high degree of skilled human intervention and technical expertise, with many lacking dedicated cybersecurity teams, and relying on ad hoc or outsourced support. TISRI suggests that SMEs may be able to address this limitation by leveraging AI-driven information security solutions. How this can be done is, for instance, include cost-effective AI-based anomaly detection solutions, automated alerts, and cybersecurity orchestration tools that will be able to integrate threat detection, analysis, and containment with minimal manual oversight. Such AI-driven solutions will automate threat detection and streamline incident response, allowing SMEs to be proactive. This will then enable SME management to shift management attention from continually being reactive to being proactive and resilience in their information security management, AI-driven efforts. TISRI provides insights on how SMEs can become resilient in these AI-driven efforts through improved learning from each incident and adopting human–AI collaboration, where, on one hand, AI automates detection and containment, and, on the other hand, human expertise will focus on strategic decision-making and continuous improvement.

6. Implications

Theory of Information Security Resilience for SME Network Infrastructure provides a comprehensive framework for SMEs to manage information security incidents more effectively by proposing the integration of governance, targeted skills development, adaptive security infrastructure, a security-conscious culture, and AI-driven incident management. These elements will help shape SMEs’ ability to build resilient and sustainable cybersecurity strategies in the resource-constrained environment of South Africa, where these SMEs operate. The implication of this study is that TISRI will bridge the gap between policy and practice by expanding the existing information security theories. TISRI integrates governance, policy alignment, and stakeholder collaboration, which SMEs often overlook, and provides insights that can help shift old ideas that SME management held away from purely technical perspectives and encourage new ideas, such as AI-driven efforts regarding information security’s human dimensions. The insights proposed are cost-effective and can help SMEs become empowered when implementing information security measures that will not require large capital investments. What is encouraged is the promotion of AI-driven efforts that can shape information security solutions.

6.1. Limitations and Future Research

This GT study involved selecting eight SMEs network security practitioners operating in Johannesburg, South Africa, using theoretical sampling. This may limit the generalisability of the findings, and TISRI model, since the sample may not fully capture the diversity of perspectives across different regions or boarder organisational contexts. However, theoretical saturation was reached through these eight network security practitioners, and no new concepts or relationships emerged from additional data, pointing that the sample was sufficient to develop TISRI. In GT, the strength lies not in sample size but in the depth of theoretical insight and the systematic link between data and emergent theory.

Future research could build on this foundational work by conducting empirical validation of TISRI model across diverse regions, contexts, and business sizes to test and refine model. Customisation for different SME sectors, such as the fintech, healthcare, and retail, could reveal how contextual factors shape information security practices and resilience. Empirical validation in emerging markets would enhance the model’s applicability in varying economic and technological settings. Finally, given the dynamic nature of network security and the rise of emerging technologies, such as AI and automation, future research could explore how SMEs might integrate AI-powered threat intelligence into the TISRI framework to strengthen adaptive and proactive security capabilities.

7. Conclusion

To conclude, this research has shown that by exploring the unique lived experiences of SME practitioners in Johannesburg and how they manage their information security network infrastructure, a theory could be modelled from this experience. Using the GT approach, this study presents TISRI as theory to improve information security practices. TISRI contains five core categories: governance, strategy and policy integration, adaptive security infrastructure, culture, capacity-building and skills development, and network security incident management, which will shape the success of network security incident response. TISRI can be used in practical settings and is adaptable for SMEs positioned to grow the South African economy by balancing policy integration, skills development, infrastructure adaptation, and AI-driven solutions. The theory proposes new insights to enhancing network security incident management and responses not previously considered. This research provides scholarly contributions through originality, resonance, and usefulness.