1. Introduction

This paper presents a timely and highly relevant analysis of the emerging role of cognitive warfare within the context of Europe’s energy transition. This topic is of critical importance to the field of applied cybersecurity and Internet governance, providing a platform for debate on ‘crucial and strategic cyber challenges facing both national institutions and multinational corporations’ [1]. The work’s interdisciplinary approach, linking geopolitics, geoeconomics, digital policy, and human rights, offers an innovative perspective that aligns perfectly with the broader mission of stimulating debate on complex cyber challenges [1]. The document’s current structure, which includes a theoretical framework, case studies, analysis of EU defences, and policy recommendations, forms a solid foundation for a comprehensive academic paper.

The EU’s green transition is not only a technical and economic project – it is also an ideological and cognitive battleground. As the EU seeks to decarbonise its economy, reduce dependence on fossil fuels, and lead global climate governance, its energy policies intersect with powerful geopolitical dynamics. These include competition over critical raw materials, contested infrastructure corridors, and rival models of green development. However, one often overlooked that the dimension of this struggle is informational: the ability to shape public opinion, investment narratives, and regulatory legitimacy through the control of digital discourse. In this context, ‘cognitive warfare’ and strategic information control emerge as critical instruments in the geoeconomic contest over the energy transition.

This study further examines corporate-led disinformation campaigns – particularly those driven by fossil fuel industries – that parallel state-sponsored cognitive operations, demonstrating measurable effects on public perception and policy delay. Integrating recent studies (e.g.: [13–18, 41]), it bridges cognitive warfare with climate misinformation research.

The paper argues that the global transition to green energy is increasingly mediated through information operations – ranging from disinformation and deep fakes to algorithmic amplification and digital platform manipulation – that seek to influence, distort, or weaponise public perception. These operations are often entangled with broader strategies of hybrid warfare, where state and non-state actors deploy digital tools not for direct military engagement but to erode confidence in institutions, fragment democratic consensus, and tilt regulatory environments in their favour. In the context of Europe’s energy transition, such tactics pose direct threats to the integrity of climate policy, the cohesion of public support, and the legitimacy of international climate cooperation.

The European Green Deal (EGD) [2], the carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) [3], and other ambitious regulatory initiatives have placed the EU at the forefront of global climate action. Yet, these policies are vulnerable to targeted cognitive disruption. Narrative attacks may portray the green transition as economically harmful, socially unjust, or environmentally ineffective – thereby weakening political commitment and delaying implementation. Moreover, the digital infrastructures through which such narratives circulate (social media platforms, recommendation algorithms, and influencer networks) are not neutral channels but active arenas of cognitive competition. The manipulation of these infrastructures, whether through bot-driven discourse, deep fake videos undermining mining supply chains, or digital suppression of climate finance platforms, constitutes a new front in energy geopolitics.

In this regard, cognitive warfare is not limited to military or intelligence operations. It increasingly includes corporate lobbying, ideological branding, and platform governance – shaping how societies perceive technological change, environmental risk, and geopolitical interdependence. The actors engaged in this domain include not only rival states, such as China and Russia, but also multinational corporations, transnational advocacy networks, and grassroots misinformation communities. Their interventions range from the subtle (e.g. seeding pro-fossil narratives through lifestyle influencers) to the overt (e.g. cyber-enabled disruption of climate conferences or activist campaigns).

This contribution situates cognitive warfare within the broader context of hybrid conflict and strategic competition, particularly as it relates to Europe’s pursuit of energy autonomy and climate leadership. It draws on conceptual frameworks from hybrid-warfare studies [4, 5], cognitive security [6, 7], and international human rights law – especially regarding freedom of information, digital privacy, and the right to a healthy environment [8]. Methodologically, it combines qualitative discourse analysis of publicly available information operations with a doctrinal review of EU legal and regulatory instruments, such as the Digital Services Act (DSA) [9], the Digital Markets Act (DMA) [10], and the AI Act [11].

The structure of the paper is as follows: Section 2 elaborates the theoretical and legal underpinnings of cognitive warfare and its relevance to geoeconomic competition. Section 3 maps key vectors of cognitive influence in the energy discourse, focusing on three areas: social media campaigns targeting nuclear versus renewable energy; deepfake content affecting trust in critical raw material supply chains; and attacks on climate finance infrastructures. Section 4 presents comparative case studies of China and Russia, analysing how each uses strategic communication to shape energy narratives in ways aligned with their geopolitical aims. Section 5 assesses the EU’s current regulatory defenses – highlighting their strengths and limitations vis-à-vis human rights standards and the risks of overreach. Section 6 proposes policy innovations for reinforcing cognitive resilience, such as embedding human rights impact assessments into climate-tech procurement and creating an EU task force on energy narrative security. The final section concludes by reflecting on the broader implications of cognitive warfare for Europe’s role in shaping the global energy transition. By framing energy geopolitics through the lens of information operations and narrative competition, this paper offers a novel contribution to the emerging field of geoeconomics [1]. It underscores that Europe’s capacity to lead the green transition will depend not only on technological and regulatory innovation but also on defending the cognitive integrity of its democratic and digital ecosystems. The control of narrative terrain – what people believe about the costs, benefits, and actors of climate action – may ultimately prove as decisive as the control of physical supply chains or market access.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

The concept of cognitive warfare has evolved significantly in recent years, becoming a central pillar of hybrid threat analysis and strategic competition in the information age. Unlike traditional forms of warfare that rely on physical force or kinetic operations, cognitive warfare targets the human mind: it seeks to alter perception, erode trust, manipulate belief systems, and ultimately influence behaviour in ways that serve the attacker’s strategic interests [7, 12]. The European energy transition, as a deeply political and economically transformative process, is increasingly vulnerable to such influence campaigns – especially in the digital space where narratives about climate, sovereignty, and prosperity are actively contested.

Recent scholarship demonstrates how corporate disinformation has functioned as a proto-form of cognitive warfare. Oreskes and Conway [13] traced how fossil fuel lobbies deployed ‘merchants of doubt’ tactics to distort climate science, while Franta [14] and Amazeen et al. [15] show the continuity between these industrial misinformation campaigns and present-day cognitive operations undermining renewable energy adoption. Studies by Geri [16] and Briggs [17, 18] further connect hybrid warfare to climate narratives and energy security, suggesting a convergence of geopolitical and corporate interests.

Cognitive warfare refers to the deliberate use of information to affect the cognitive domain – that is, how individuals and societies process information, form judgements, and make decisions [19]. It encompasses techniques such as disinformation, misinformation, psychological operations (PSYOPS), attention hijacking, and algorithmic manipulation. In the context of energy geopolitics, these techniques are deployed to undermine trust in renewable technologies, create confusion around regulatory efforts like the EGD, or promote narratives that favour continued fossil fuel dependence.

As argued by Gerasimov [6] in the influential Russian military doctrine on hybrid conflict, the boundaries between war and peace have blurred. The battlefield has extended into civilian domains – particularly media, education, and digital platforms – where influence operations can precede, substitute, or complement traditional coercive means. Similarly, China’s doctrine of ‘Three Warfares’ (public opinion, legal, and psychological warfare) emphasises narrative dominance as a cornerstone of strategic competition [20]. These frameworks suggest that controlling the information environment is as important as controlling physical resources or territories. The expansion of military operations into new digital frontiers, such as the metaverse, further underscores this evolving landscape of conflict [21].

Hybrid threats, as defined by the European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats (Hybrid CoE), are activities conducted by state or non-state actors that fall below the threshold of war but aim to disrupt or influence political decision-making, economic resilience, or social cohesion [5]. The energy transition is especially vulnerable to such threats because it disrupts established interests and requires sustained public trust. Strategic actors may thus use hybrid tactics – combining cyberattacks, disinformation, lawfare, and economic coercion – to delay, derail, or reframe the energy transition. For example, disinformation campaigns targeting the safety of lithium-ion batteries or the environmental impact of wind turbines are not random acts of confusion but strategic efforts to shape public perception, regulatory outcomes, and market preferences. These operations often amplify the existing societal divisions (e.g. between urban and rural communities, or North and South member states), thereby weakening EU cohesion and slowing down green legislation [22, 23].

Traditionally, geoeconomics has focused on the use of economic tools for strategic ends – such as sanctions, trade policy, or investment screening [1]. However, in the digital age, information has itself become a geoeconomic asset. Shaping the global narrative around the energy transition, for instance, can influence flows of investment, consumer choices, and regulatory alignments across regions. This is particularly visible in emerging markets, where Chinese state media promote Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)-funded green infrastructure as more affordable and pragmatic than EU-backed alternatives [23]. Similarly, Russian-backed media has framed EU climate policies as elitist and harmful to energy security – promoting continued engagement with fossil-rich regimes [7, 22–24]. Information control thus becomes a form of non-market power: it influences economic outcomes not by altering prices or tariffs but by reconfiguring the discursive environment in which economic decisions are made. In this sense, narrative control is a form of soft coercion – shaping the epistemic conditions under which markets, regulations, and alliances operate [7].

The deployment of cognitive warfare techniques against EU publics raises profound ethical and legal questions. On the one hand, freedom of expression and access to information are protected under international human rights law, including Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR, 1948) [25] and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR, 1966) [26]. On the other hand, states have a duty to protect their populations from systematic disinformation and psychological manipulation, especially when it undermines democratic deliberation or environmental integrity [27]. This tension is particularly salient in the European digital regulatory landscape. Instruments like DSA and DMA aim to enhance platform accountability and reduce systemic risks caused by algorithmic amplification of harmful content. Yet, critics warn that overly intrusive regulation may threaten privacy, chill-free speech, or introduce forms of state surveillance that contradict EU fundamental rights [28]. Moreover, emerging legislation on AI transparency and ‘trustworthy AI’ must reconcile national security imperatives with ethical concerns about neurological manipulation and behavioural targeting [29]. The challenges and opportunities of AI applications in cybersecurity are a critical area of ongoing research [30]. Thus, the EU finds itself in a paradox: defending cognitive sovereignty in the face of foreign information operations while upholding liberal values in its internal governance. Navigating this tension will be critical to building ‘cognitive resilience’ – defined not as censorship but as the capacity to sustain informed, democratic discourse under conditions of information overload and strategic interference [31].

While overlapping in practice, cognitive warfare, information warfare, propaganda, and disinformation are conceptually distinct phenomena. Cognitive warfare refers to the deliberate manipulation of the cognitive domain – perception, judgement, and belief – to influence decision-making and collective behaviour. Information warfare encompasses the broader competition over the information environment, including cyber operations and influence tactics. Propaganda and strategic communication represent legitimate soft-power tools used by states to promote narratives consistent with their interests. Disinformation, in contrast, constitutes the operational vector of cognitive warfare, weaponising false or misleading content to shape perceptions and erode trust. This analytical differentiation builds upon Marsili’s earlier works, which conceptualise cognitive and hybrid warfare as multidimensional phenomena extending beyond the military sphere to the informational and cognitive domains [19], and further explore their expansion into virtual/immersive theatres [21]. These studies demonstrate that, in the digital age, control over the narrative domain has become a decisive determinant of geopolitical outcomes. As Marsili argues [19, 21], the struggle for cognitive and informational dominance increasingly defines strategic competition, extending conflict into the psychological and perceptual spheres that underpin political decision-making and social cohesion.

3. Analysis of Cognitive Influence Vectors

Narratives are not neutral – they shape perceptions of legitimacy, define the boundaries of acceptable policy, and influence political and market behaviour. In the context of Europe’s energy transition, narrative control has become a target of cognitive operations aimed at manipulating public opinion, polarising debate, and undermining trust in green technologies and institutions. This section maps three strategic vectors of cognitive influence deployed by state and non-state actors against the EU’s energy agenda: discursive manipulation of nuclear versus renewables debates; deepfake and disinformation campaigns against critical raw material (CRM) supply chains; and targeted disruption of digital infrastructures supporting climate finance.

One of the most prominent fronts in the cognitive contest around energy policy is the debate over the legitimacy of nuclear power as part of the green transition. While the European Commission included nuclear energy in its sustainable taxonomy under certain conditions [32], public and political attitudes remain highly polarised, creating fertile ground for influence operations. Coordinated social media campaigns – often involving inauthentic accounts or state-linked media – have promoted narratives framing nuclear energy either as a green saviour or a dangerous relic. Russian-affiliated outlets, such as RT Deutsch and Sputnik, have historically amplified anti-nuclear sentiments in Germany and Austria, echoing long-standing social anxieties about nuclear disasters and waste [7, 22–24]. Simultaneously, other actors have promoted pro-nuclear narratives portraying renewables as intermittent, unreliable, and dependent on Chinese supply chains. These narratives are often shaped by algorithmic amplification, whereby divisive or emotionally charged content receives more visibility [19, 24, 31, 33]. Studies show that nuclear-related hashtags on platforms like Twitter/X and TikTok are systematically targeted by coordinated campaigns, including those with commercial or geopolitical agendas [22]. The result is a polarised and cognitively fragmented energy debate, where public discourse becomes less about empirical evidence and more about identity politics. This undermines rational deliberation and opens space for actors seeking to delay decarbonisation or fragment EU consensus on energy policy.

Another cognitive battleground involves critical raw materials – especially lithium, cobalt, and rare earth elements essential for green technologies such as batteries, wind turbines, and electric vehicles (EVs). Given Europe’s strategic vulnerability in CRM supply chains (often reliant on China, the DRC, or Latin America), disinformation campaigns have targeted these dependencies to weaken public and investor confidence. Several disinformation operations – some traceable to actors with pro-fossil or authoritarian leanings – have circulated deepfake videos and forged documents purporting to show environmental abuses, child labour, or political corruption associated with EU-linked mining operations. While genuine concerns about human rights in the extractive sector exist and merit scrutiny, the strategic use of fabricated or decontextualised content aims to erode the legitimacy of EU green-tech procurement.

These operations serve multiple purposes: delegitimising European efforts to establish ‘clean’ or ‘ethical’ CRM supply chains; promoting narratives that Chinese or Russian state-led mining is more stable or transparent; and undermining consumer confidence in electric mobility and energy storage. Moreover, platform design features – such as auto-play algorithms, influencer endorsements, and minimal content verification – allow deepfakes and manipulated media to go viral before correction mechanisms activate. While platforms like YouTube and Meta have introduced fact-checking partnerships, their reach is limited across non-English-speaking EU markets. This vulnerability demonstrates that Europe’s cognitive defences in the green economy must extend beyond regulation: they require real-time monitoring, open-source intelligence (OSINT), and civic verification capacities, particularly in multilingual, cross-border contexts.

A more structural but equally potent form of cognitive interference targets digital infrastructures underpinning green finance. These include platforms supporting environmental, social, and governance (ESG) reporting, sustainable investing, and carbon offset mechanisms. In recent years, several cyber-enabled influence operations have aimed to discredit these instruments or to hinder their access and usability. For example: ESG data providers such as Refinitiv or Sustainalytics have been targeted by bot-generated disinformation campaigns, accusing them of green washing or politicisation; online repositories of carbon offset registries have been subjected to denial-of-service (DoS) attacks, affecting accessibility during major climate finance events.

Influencers linked to fossil industry lobbies have orchestrated viral TikTok campaigns mocking ESG metrics as ‘climate communism’ or ‘woke capitalism’. While not always attributable to foreign states, these campaigns contribute to a discursive environment of confusion and cynicism, where finance professionals, journalists, and citizens alike begin to distrust the metrics and institutions that support climate capital flows. This dynamic can be read through the lens of informational geoeconomics: by disrupting Europe’s green finance architecture cognitively and digitally, adversarial actors can slow capital reallocation, preserve fossil rent-seeking positions, and challenge EU normative leadership on sustainable development [1].

A key feature of cognitive warfare is its deniability and delegation. Influence campaigns are often run through proxy actors – public relations (PR) firms, bot farms, shell media organisations, or transnational ideological movements. This complicates attribution and blurs legal responsibility. For instance, non-state actors such as climate denial networks, populist influencers, or radical libertarian groups have adopted messaging strategies aligned with foreign disinformation narratives; private sector platforms, incentivised by engagement metrics, may unknowingly propagate these narratives through opaque content promotion systems; diasporic or fringe media ecosystems (e.g., Telegram channels, WhatsApp groups) allow messages to evade platform moderation and spread rapidly in local contexts. These indirect channels represent a force multiplier for adversarial states that lack direct access to Western public spheres but can effectively shape ambient political discourse through culturally proximate messengers.

4. Comparative Case Studies: China and Russia

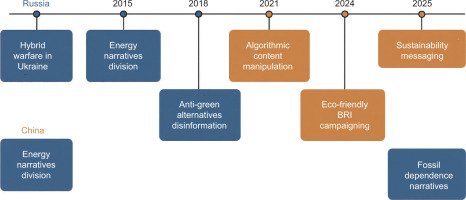

While cognitive operations are transnational in nature and often difficult to attribute with certainty, several high-profile campaigns linked to China and Russia offer insight into how digital influence tools are deployed to shape Europe’s energy discourse. These actors differ in strategic intent and narrative approach: China seeks to position itself as an indispensable green technology partner, while Russia leverages disinformation to undermine the EU’s energy security and decarbonisation goals, often reinforcing fossil fuel dependence. This section analyses representative operations and discursive strategies associated with each actor, drawing on OSINT, platform data, and doctrinal analysis.

China’s global infrastructure initiative, the BRI, has increasingly adopted a ‘green’ branding – emphasising renewable energy, smart grids, and low-carbon transport projects in developing countries. Beijing seeks to project itself not only as a geoeconomic investor but as a normative leader in sustainable development [33]. In the EU context, Chinese influence campaigns have promoted this image using the following three primary strategies. Firstly, through official media channels such as Xinhua and CGTN, China has disseminated narratives, positioning itself as the global leader in green innovation, particularly in photovoltaics, EVs, and lithium battery production. These narratives highlight the environmental benefits of BRI-funded solar farms and EV infrastructure; China’s dominance in critical raw material processing; and the ‘win–win’ nature of Sino-European climate cooperation. This messaging is amplified via multilingual content on YouTube, LinkedIn, and TikTok, often targeting young or technophile audiences. It strategically appeals to Europe’s climate policy ambitions while obscuring dependency risks.

Secondly, Chinese embassies and Confucius Institutes in Europe have organised panels, webinars, and university partnerships on green finance and technology. While presented as educational outreach, these events often reproduce state-sanctioned talking points on topics like green BRI as a contribution to the Paris Agreement; Western ‘double standards’ on environmental regulation; and the superiority of Chinese state-led green governance. This tactic constitutes a form of cognitive soft power, shaping elite opinion within policy, academic, and corporate circles [24].

Thirdly, Chinese actors have demonstrated growing sophistication in gaming the recommendation algorithms of Western platforms. Videos and news stories promoting Chinese green ventures are often keywords optimised to appear alongside EU climate policy content. For example: BRI-related infrastructure videos frequently co-appear in YouTube searches for ‘EU Green Deal’ or ‘Fit for 55’; sponsored TikTok content using ‘eco-friendly,’ ‘sustainability,’ or ‘ESG’ hashtags subtly embeds pro-China narratives. This illustrates how informational positioning can function as a geoeconomic tactic: by controlling narrative proximity, China influences perception of compatibility or complementarity between its goals and the EU’s climate strategy.

Russia’s information operations around European energy policy have taken a more disruptive and subversive form, building on longstanding practices in hybrid warfare. Since at least 2014, Russian-linked media and influence networks have sought to erode trust in European institutions, promote division among EU member states, and undermine support for renewables in favour of fossil fuels [34, 35]. Three key operational patterns stand out in the energy domain: firstly, Kremlin-affiliated outlets such as RT and Sputnik have consistently amplified divisive debates within the EU on energy topics – such as Germany’s nuclear phase-out versus France’s nuclear investments; opposition to wind farms in rural or coastal areas; and migration of green industries due to carbon border taxes. By exploiting real controversies, these campaigns seed distrust between citizens and institutions, portraying EU climate policies as elitist, economically harmful, or geopolitically naïve [22]. Social media bots and trolls reinforce these narratives in national languages, using localised memes and hashtags [31, 36].

Secondly, following the outbreak of the war in Ukraine and the EU’s push to reduce dependence on Russian fossil fuels, disinformation targeting green alternatives surged. Russian actors began promoting narratives asserting that wind turbines are environmentally destructive; solar panels rely on exploitative Chinese labour; and EVs will fail in European winters. In some cases, doctored videos or fake expert interviews were circulated to support these claims. The aim was not to promote a coherent alternative but to delegitimise energy diversification altogether. This tactic aligns with Russia’s historical use of reflexive control – a doctrine that seeks to manipulate adversary decision-making by flooding information space with contradictory messages, making rational consensus difficult [37].

Thirdly, despite the EU’s embargoes and decoupling efforts, Russian actors continue to promote narratives urging a return to ‘rational’ partnerships with fossil fuel-rich states. These are couched in energy realism: ‘Europe cannot survive without gas and oil’; economic fatalism: ‘green energy will bankrupt the middle class’; and anti-colonialism: ‘EU climate policies hurt the Global South.’ These messages are spread via proxy influencers, including European far-right and far-left political figures; ‘alternative media’ sites opposing mainstream environmentalism; and coordinated Telegram channels and fringe platforms. By portraying the EU’s energy transition as economically destructive, geopolitically destabilising, and ideologically arrogant, Russian disinformation aims to erode public support and delay regulatory action. These differences reflect divergent geopolitical ambitions. China seeks to embed itself within Europe’s green economy, shaping dependency and standards from within. Russia, conversely, acts as a spoiler power, aiming to prevent Europe from achieving energy autonomy and strategic coherence.

Table 3 provides a clear and concise comparison of the strategies employed by these two state actors.

Table 1

Conceptual frameworks on cognitive and information warfare.

| Framework/author | Core concept | Relevance to energy transition |

|---|---|---|

| Gerasimov [6] | Hybrid warfare blurs war–peace divide | Informational front integrated into strategic conflict |

| Chinese ‘Three Warfares’ [20] | Public opinion, psychological, and legal warfare | Use of narrative dominance for strategic legitimacy |

| Marsili [19, 21] | Cognitive warfare and metaverse domains | Expansion of conflict into cognitive and perceptual spheres |

| Rickli et al. [7] | Cognitive security governance | Protection of perception and trust in democratic institutions |

| Bradshaw et al. [31] | Industrialised disinformation | Organisational manipulation of online discourse |

Table 2

Main vectors of cognitive influence in the EU energy transition.

Table 3

Comparison of the strategies employed by China and Russia.

Table 4

EU regulatory instruments addressing cognitive and information threats.

Figure 1 illustrates key disinformation and influence operations targeting the EU’s energy transition, distinguishing between Russia’s disruptive reflexive-control tactics and China’s long-term narrative co-optation strategies.

While these cases illustrate state-driven cognitive operations, similar mechanisms are also observable in the private sector, where corporate actors deploy disinformation to influence energy narratives and policy outcomes.

4.1. Corporate Disinformation and Fossil Fuel Narratives

A recurring challenge in responding to cognitive warfare lies in attribution and accountability. While many campaigns originate from known actors, their dissemination often occurs through third-party platforms, influencers, or even unwitting users. This raises important legal and ethical dilemmas: how can democracies counter disinformation without infringing freedom of expression? What responsibilities do platforms have to prevent narrative manipulation? Can international law evolve to treat cognitive interference as a breach of sovereignty? The Tallinn Manual 2.0 on cyber operations [38] and the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (also known as the ‘Ruggie Principles’) [39] offer partial guidance, but lack binding force. The DSA and EU Code of Practice on Disinformation [40] mark steps towards a normative framework – but their effectiveness depends on platform compliance and transnational coordination.

Beyond state actors, corporate entities – particularly in the fossil fuel sector – have long engaged in information operations that parallel state-led cognitive warfare. These campaigns, often orchestrated by major oil and gas corporations, such as Exxon Mobil, BP, and Shell, aimed to delay climate policy and undermine public confidence in renewable energy. As Oreskes and Conway [13] and Franta [14] demonstrate, corporate disinformation constructed epistemic uncertainty around climate science, effectively manipulating cognitive frames in ways similar to Russian maskirovka or reflexive control doctrines.

Amazeen et al. [15] further reveal how corporate messaging exploits emotional narratives to sustain fossil fuel legitimacy, whereas Xi et al. [41] empirically show that climate policy uncertainty significantly affects renewable energy adoption. This evidences the real-world cognitive impact of such campaigns, confirming that corporate-led disinformation operates as a strategic component of cognitive warfare.

Recognising these dynamics allows for a broader understanding of cognitive warfare as an ecosystem that includes not only state but also corporate and hybrid actors whose economic interests intersect with geopolitical influence.

5. European Regulatory Frameworks and Human Rights Dilemmas

In response to growing awareness of cognitive threats and digital interference, the EU has begun developing legal, institutional, and communicative countermeasures. These range from regulatory interventions, such as the DSA and the Code of Practice on Disinformation, to digital literacy campaigns, transparency obligations, and support for fact-checking networks. However, as these defences evolve, they raise critical tensions with fundamental rights frameworks, including freedom of expression, privacy, and access to information. This section examines the EU’s current defence posture against cognitive interference in the energy transition domain, and the normative dilemmas it entails. It situates the discussion within international legal instruments and the EU primary law while highlighting structural limitations and unresolved trade-offs.

While cognitive warfare and information warfare overlap, the former specifically targets the cognitive and affective processes of individuals – perception, belief, and judgement – rather than simply the flow of information. Cognitive resilience, therefore, refers to the individual and societal capacity to recognise and resist manipulation, whereas information resilience pertains to the structural robustness of communication systems.

The DSA, adopted in 2022 and entered into force on 16 November 2022, represents the EU’s flagship regulatory effort to ensure transparency and accountability in online content governance. It imposes obligations on very large online platforms (VLOPs) – including Meta, Google, X, and TikTok – to monitor and mitigate systemic risks (e.g. disinformation, and manipulation of democratic processes), provide researchers with access to platform data, and be transparent about content moderation algorithms and takedown decisions. VLOPs were required to comply from 23 August 2023, while most other services had complied until 17 February 2024. The DSA’s risk-based approach is particularly relevant for countering cognitive warfare in energy transition, as it allows for proactive risk assessments of narratives that may distort public understanding or policy debates. For example, false claims undermining climate science or promoting fossil fuel dependency may be subjected to algorithmic downranking or flagged for user warning.

Furthermore, the European Commission published its final guidelines on the protection of minors under the DSA on 14 July 2025, which include the concept of a ‘risk review’ that providers must conduct periodically, at least annually, or whenever significant changes are made to their service’s design [42]. Nevertheless, implementation remains uneven. As of mid-2025, compliance audits revealed limited cooperation by some VLOPs, especially regarding access to real-time data on green-related misinformation [43]. Companies that do not comply with the new obligations risk fines of up to 6% of their global annual turnover.

Complementary to regulation, the EU Code of Practice on Disinformation – adopted in 2018, strenghtened in 2022, and revised in 2025 – functions as a co-regulatory mechanism, where platforms, advertisers, and civil society organisations voluntarily commit to combat harmful content. It includes measures such as demonetising misleading green-tech content, labelling AI-generated media and manipulated visuals, and strengthening collaborations with fact-checkers and academic monitors. Although not legally binding, the Code’s provisions are referenced under the DSA as best practices and can become enforceable through platform-specific risk assessments. The Code has led to modest improvements in flagging of misleading energy narratives. For instance, coordinated campaigns questioning the feasibility of the CBAM were demoted on Meta platforms in late 2024 after external alerts from EU Disinfo Lab [44].

The EU has also established the AI Act (Regulation (EU) 2024/1689), the first-ever comprehensive legal framework on AI worldwide, which entered into force in 2025 with staggered application. The first obligations took effect on 2 February 2025, prohibiting certain practices and uses of AI technology and solidifying the importance of AI literacy in organisations [45]. Key bodies such as the AI Office and AI Board officially became operational on 2 August 2025, playing a central role in implementation and enforcement, particularly for general purpose AI models [45]. The AI Act defines four levels of risk for AI systems: unacceptable, high, limited, and minimal. Practices considered a clear threat to safety, livelihoods, and rights are banned, including harmful AI-based manipulation and deception, harmful AI-based exploitation of vulnerabilities, and social scoring. For limited-risk AI, specific disclosure obligations ensure that humans are informed when interacting with AI systems like chatbots, and providers of generative AI must ensure that AI-generated content is identifiable and clearly labelled, especially deepfakes and text published to inform the public on matters of public interest. It should also be noted that the official text of the AI Act was published in June 2024.

The document highlights the critical tensions between EU digital defences and fundamental rights enshrined in EU and international law, including Article 11 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (CFR) [46], Article 8 (protection of personal data), Article 19 of the ICCPR, and Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) [47]. These rights may come into conflict with platform moderation, algorithmic content control, or state-led counter-disinformation campaigns. Efforts to remove or suppress misleading content – such as claims denying anthropogenic climate change or promoting fossil fuel nationalism – may be perceived as censorship or suppression of dissenting political opinions. This is especially contentious when targeting fringe scientific voices, political opposition, or citizen activists critical of EU energy policy.

Although the DSA includes safeguards for user redress and transparency, critics warn that moderation discretion is often delegated to private platforms, with insufficient public oversight (Kaye, 2023) [48]. This could undermine the democratic legitimacy of content governance in the energy debate. Enhanced monitoring of online activity – especially for early detection of coordinated inauthentic behaviour – may entail surveillance of user communications or reliance on automated detection systems. These techniques raise questions under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) [49], the ePrivacy Directive [50], and customary humanitarian law, which protect civilians from indiscriminate surveillance during peacetime and conflict. Embedding human-rights impact assessments within digital governance not only safeguards privacy and freedom of expression but also mitigates the risk of cognitive manipulation by ensuring transparency, accountability, and participatory oversight in algorithmic decision-making.

The use of behavioural profiling to identify susceptibility to green disinformation – for instance, among sceptical rural populations – could also risk stigmatising vulnerable groups or reinforcing cognitive biases, rather than mitigating them [51]. The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) has explored the responsibility of platforms for user-generated content and the principle of proportionality in cases such as Delfi AS v. Estonia (2015) [52] and Magyar Helsinki Bizottság v. Hungary (2016) [53].

A deeper normative dilemma concerns the balance between state responsibility to protect democratic discourse and the individual’s right to cognitive sovereignty – the freedom to form opinions without manipulation. While EU policies aim to ‘immunise’ citizens against harmful narratives, they may unintentionally adopt paternalistic assumptions about information consumption and rationality. This dilemma is exacerbated by the use of strategic communication by EU institutions themselves, which, although aimed at transparency and debunking, often blur into narrative competition. When facts are embedded within framing choices, epistemic neutrality becomes elusive [7].

Despite ambitious regulatory developments, several structural gaps remain in the EU’s defence architecture, such as the lack of a dedicated task force for energy narrative security, limited engagement with the Global South, and insufficient investment in cognitive resilience R&D. While the EU has units for cybersecurity (CERT-EU), foreign interference (StratCom), and disinformation (EEAS), there is no task force specifically addressing cognitive threats to the energy transition. This fragmentation weakens coordination between DG CLIMA, DG ENER, and DG CONNECT as well as member state agencies. Many influence campaigns around critical raw materials and climate finance play out in third countries, where local media, civil society, and fact-checkers lack resources or EU support. Disinformation about the carbon border tax or lithium sourcing ethics spreads with little corrective presence, weakening Europe’s legitimacy as a green leader [54]. Finally, the EU’s investments in digital and energy security R&D remain siloed. Programs like Horizon Europe Programme [55] or the Digital Europe Programme [56] could fund interdisciplinary research on cognitive resilience but currently prioritise technological over sociopolitical innovation. As a result, tools for detecting deepfakes, mapping narrative flows, or simulating public opinion shifts are underdeveloped in policy applications.

6. Policy Recommendations for Strengthening Cognitive Resilience

Building on the preceding analysis of cognitive warfare’s role in Europe’s energy transition and the current defensive measures and their human rights dilemmas, this section outlines a series of policy recommendations aimed at strengthening Europe’s cognitive resilience. These proposals seek to balance effective countermeasures against disinformation and manipulation with the protection of fundamental rights while enhancing strategic autonomy and inclusive governance.

Firstly, given the profound normative and practical tensions identified in content regulation and data governance, the EU should systematically integrate human rights impact assessments (HRIA) into all phases of climate–technology development and procurement. This would ensure that digital tools used for monitoring, moderation, or public engagement do not infringe on privacy, freedom of expression, or due process; algorithmic transparency is mandated through clear standards for explainability and auditability; and potential unintended consequences – such as reinforcing socio-economic biases or marginalising vulnerable populations – are anticipated and mitigated. The United Nations have published key texts, including standards, analysis, and recommendations emerging from the United Nations human rights mechanisms, providing a practical framework for operationalising these assessments [57]. Institutionalising HRIA within DG CLIMA and DG CONNECT, as well as member states’ energy agencies, would foster coherence across technological innovation and policy safeguards.

Secondly, current EU institutions addressing cybersecurity, disinformation, and strategic communication operate largely in silos, limiting their capacity to coordinate a focused response to cognitive threats in the energy domain. The creation of a dedicated Energy-Narrative Security Task Force would monitor and analyse evolving narrative trends and hybrid-information operations specifically targeting Europe’s energy transition policies; coordinate intelligence-sharing between EU bodies, member states, digital platforms, and civil society fact-checkers; develop early warning mechanisms to identify emerging disinformation campaigns undermining climate policy or energy market stability; and provide rapid response protocols combining public diplomacy, digital countermeasures, and media engagement. This task force should adopt a multidisciplinary approach, incorporating expertise from political science, data analytics, communications, and international law, and could be modelled on the existing Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT) structures but with a specific cognitive and geoeconomic remit.

Thirdly, disinformation related to critical raw materials sourcing, green infrastructure financing, and climate adaptation increasingly involves third countries in Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia. EU policies must therefore strengthen support for local fact-checking organisations and independent media in these regions, enabling them to expose and counter hybrid-information operations linked to Chinese BRI projects or Russian fossil fuel lobbying. Furthermore, fostering capacity-building programs emphasising cross-border cooperation, data sharing, and digital security, and encouraging co-creation of narratives that reflect local priorities and realities, rather than imposing Eurocentric perspectives, would improve legitimacy and uptake. Such cooperation would align with the EU’s broader external action goals of promoting democratic governance and human rights globally while enhancing the integrity of supply chains critical to the green transition.

Fourthly, to keep pace with increasingly sophisticated disinformation tactics – such as deepfakes, synthetic media, and AI-driven microtargeting – the EU should boost funding for research and development in automated detection systems capable of identifying coordinated inauthentic behaviour related to energy narratives; sociotechnical tools that map the flow of green-related narratives across platforms and linguistic communities; and public-facing applications designed to increase citizen awareness and critical consumption of digital content. Funding instruments like Horizon Europe Programme and the Digital Europe Programme should prioritise projects that bridge technical innovation with social science insights, enabling scalable and context-sensitive solutions. Collaboration with NATO’s Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence and academic networks could amplify impact.

Fifthly, beyond regulatory and technical measures, cognitive resilience depends fundamentally on a healthy information ecosystem where diverse voices and perspectives flourish. The EU should support public broadcasting and independent journalism focused on energy transition topics, especially those that can challenge misleading or oversimplified narratives. It should also encourage community-based initiatives that empower citizens to co-create and share fact-based content tailored to regional and cultural contexts, and develop public forums and deliberative spaces that enhance dialogue between policymakers, industry actors, and civil society, fostering mutual understanding and trust. Such efforts contribute to democratic resilience by reducing polarisation and epistemic fragmentation, mitigating the social conditions that enable cognitive warfare.

Finally, given the transnational nature of cognitive warfare, the EU must champion international frameworks to regulate strategic communication and hybrid-information operations consistent with human rights and humanitarian law. This includes advocating for global norms to uphold information integrity and counter disinformation, particularly when used as a tool of economic or political coercion in critical sectors like climate and energy, as highlighted in UN policy briefs and General Assembly discussions on information integrity [58–60]; enhancing cooperation with partner states and multilateral organisations (e.g. UN and Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe [OSCE]) on capacity-building and information-sharing; and promoting ethical guidelines for AI and digital platforms that encompass environmental integrity and public interest considerations. Such leadership would bolster the EU’s credibility as a global actor in the energy transition while constraining malign state and non-state actors exploiting cognitive vulnerabilities.

By embedding these recommendations into a coherent policy framework, the EU can strengthen its cognitive defenses without sacrificing core democratic principles. Addressing the complex interplay between digital technologies, geopolitical competition, and human rights is essential to securing Europe’s strategic autonomy in green transition. The following final section summarises key findings and highlights avenues for future research and policy development.

7. Conclusions

This paper has examined the emerging role of cognitive warfare and information control in shaping the geopolitics of Europe’s energy transition. It has argued that Europe’s journey towards a sustainable and secure energy future depends not only on technological innovation and raw material access but also fundamentally on the contestation over narratives, perceptions, and knowledge in the digital information environment. As such, the cognitive domain has become a critical front in the broader geoeconomic competition influencing global energy governance.

The theoretical framework grounded in hybrid warfare concepts and human rights norms highlighted the complex interplay between state and non-state actors seeking to manipulate public opinion, regulatory agendas, and market dynamics through sophisticated disinformation, algorithmic amplification, and platform manipulation. This hybrid-information warfare challenges traditional notions of sovereignty and democratic governance by exploiting digital vulnerabilities and social fragmentation.

Comparative case studies of China and Russia illustrated distinct but complementary strategies targeting Europe’s energy transition. China’s promotion of BRI-funded green infrastructure leverages positive narratives and infrastructure investments to shape dependency and influence, while Russian operations focus on sowing doubt about the reliability and costs of the EGD, encouraging alignment with fossil fuel producers. These case studies demonstrate that cognitive warfare is not limited to direct attacks but also includes narrative framing designed to fragment consensus and delay climate action.

The analysis of European defensive mechanisms revealed a patchwork of digital literacy campaigns, platform regulation efforts, and emerging legislative initiatives like the DSA. However, these responses are constrained by competing priorities to safeguard freedom of expression, privacy, and due process rights, creating dilemmas that risk either undercutting democratic values or leaving cognitive vulnerabilities unaddressed. This tension underscores the need for a rights-respecting yet robust framework for cognitive resilience.

The policy recommendations put forward seek to navigate these challenges by embedding human rights impact assessments into climate technology governance, establishing a dedicated EU task force on energy-narrative security, and enhancing partnerships with fact-checking networks, especially in the Global South. Investing in interdisciplinary research and promoting pluralistic, transparent information ecosystems further strengthens societal immunity against manipulation. At the international level, fostering ethical standards and cooperation is essential to curtail the weaponisation of information in global energy competition.

Ultimately, Europe’s strategic autonomy in the energy domain hinges on its capacity to control the digital ‘battlefield of ideas’ as much as its access to physical resources and technological expertise. Cognitive resilience – understood as the ability of societies, institutions, and individuals to anticipate, withstand, and recover from disinformation and manipulation – must become a central pillar of Europe’s energy and security strategy. This requires innovative governance approaches that integrate technological, legal, and societal dimensions, respecting human rights while confronting evolving hybrid threats.

This study contributes to the workshop’s call by bridging the gap between geopolitics and geoeconomics through the lens of cognitive warfare, illustrating how information operations will shape not only Europe’s energy future but also the global order. Further research should explore the micro-level impacts of cognitive manipulation on public attitudes towards energy policies and investigate best practices for collaborative resilience across digital platforms, governments, and civil society. In conclusion, the green transition is as much a battle over ideas as it is a race for resources. Europe’s leadership in the global energy transition depends on its ability to safeguard the integrity of information flows and foster informed, democratic deliberation. While conceptual in nature, this study lays the groundwork for future empirical analyses. Subsequent research could test correlations between disinformation intensity and shifts in public sentiment regarding energy policy adoption, using sentiment analysis and media network mapping. By doing so, it can build a future that is not only environmentally sustainable but also cognitively secure and socially just.